Abstract

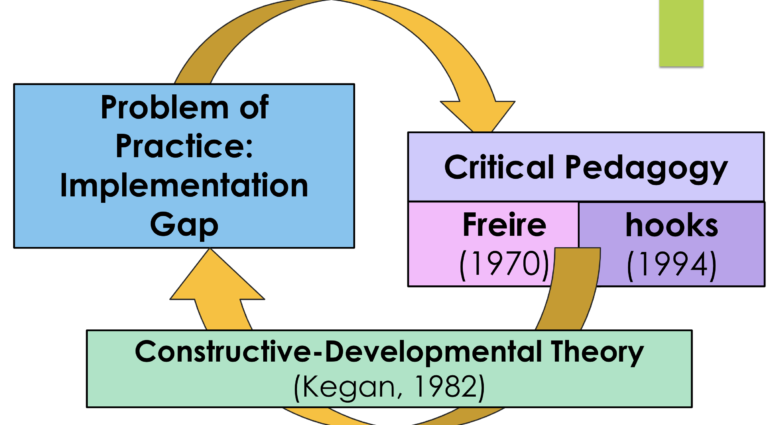

The purpose of this study is to interrogate the relationship between adult development theory and critical pedagogy. My methodology is a close reading and document analysis supported by theory. Adopting Kegan’s constructive-developmental framework as an analytical lens, I perform a close reading of Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970) and hooks’ Teaching to Transgress (1994). Considering the role of subject-object relationships in both Kegan’s theory and Freire’s liberatory pedagogy, I suggest that educators must possess significant developmental capacity to construct authentically liberatory educational spaces. I explore this suggestion further by analyzing what hooks’ personal essays reveal about the relationship between her developmental stage and her critical teaching practice. I find that hooks’ capacity for intersubjective meaning-making is key to her pedagogy. Moreover, I find that hooks’ thorough study of Freire and fervent commitment to liberatory pedagogy engender her developmental growth, enhancing her capacity both to teach and to know intersubjectively. I conclude by discussing potential implications for aspiring critical educators.

For Our Students and Ourselves: A Constructive-Developmental Reading of Teaching to Transgress

How can teachers, instructional coaches, and school leaders implement more critical pedagogies in their classrooms? Many practitioners voice a desire to critique and evolve traditional instructional paradigms. This desire is especially strong – and urgent – for educators serving marginalized communities. For such populations, canonical content and classic, teacher-centered methods perpetuate hegemonic power structures, furthering exclusion and oppression and precluding a liberatory education (Freire, 1970).

The purpose of this study is to interrogate the role that adult development plays in practitioners’ efforts to implement critical teaching methods. To examine the relationship between developmental and pedagogical capacity, I perform a theory-informed textual analysis of bell hooks’ (1994) Teaching to Transgress. I analyze hooks’ landmark essays, which chronicle her attempt to develop a critical methodology as a university professor. Specifically, I analyze hooks’ narrative through the lens of Kegan’s (1982) constructive-developmental theory. My analysis focuses on hook’s developmental meaning-making systems, her negotiation of subject-object relationships in the classroom, and her capacity for implementing critical pedagogic methods.

My guiding questions are the following:

- What does hooks’ language suggest about her ways of knowing and adult development at various stages in her career?

- How do hooks’ ways of knowing influence her perspectives on her own critical pedagogy?

- What do hooks’ reflections suggest about the adult developmental demands that accompany a practitioner’s efforts to implement critical methods?

Overview

The paper has five sections. In section one, I offer a personal disclosure in the form of a narrative, explaining how my recent experiences as a practitioner contributed to the conception of this paper. I share how a timely reading of hooks’ Teaching to Transgress sparked my desire to explore the relatedness of critical pedagogy and adult development theory. In section two, I provide a brief overview of Kegan’s constructive-developmental framework. In section three, I put Freire’scritical pedagogyin dialogue with Kegan’s theory, focusing on the nature of intersubjective meaning-making in both. In section four, I perform a close reading of hooks’ Teaching to Transgress, analyzing her essays through a constructive-developmental lens. In section five, I synthesize my findings and discuss implications for education leaders.

Section One: A Fraught Training and Timely Reading

This section takes the form of a personal narrative, in which I disclose and reflect upon the series of personal-professional experiences that gave rise to this project. By leading with my personal narrative, I am elevating my own experiential knowledge and working within a constructivist inquiry paradigm. I adopt Reason’s (1988) stance of critical subjectivity, which encourages the sharing of primary experiences in one’s inquiry process (see also Maxwell, 2008).

A Fraught Training

The session had been polarizing. After clicking through the final slide, my co-facilitator and I left the banquet hall quickly, snaking through the round conference tables to the nearest double doors. Once outside, we sank into a pair of empty chairs and looked at one another. Next came a flood of feelings: discomfort, disappointment, pride.

Clunkily titled Great Teaching, we had designed our session to articulate a significant shift in our charter school network’s pedagogical values. I had joined the network only six months before, and I had spent much of my real estate at superintendent meetings decrying the abundance of industrial, directive, I-we-you curricula. My co-facilitator had worked at the network for years, and she had long shared this critique of the academic program. In fact, she had pursued a superintendency primarily to advocate for the progressive curricular changes that she had previously spearheaded, somewhat undercover, as a principal.

She and I had thus become de facto advocates for an in-house pedagogical revolution. We wanted to shift the organization’s default and to move urgently toward a student-centered instructional core. Weeks prior to this training, we had been thrilled to see our pedagogy initiative earn top billing in the network’s five-year strategic plan. We had been grateful, too, for the platform to launch the initiative at our annual school leader summit.

We knew the session would be tricky. Our call-to-arms would necessarily critique some of our colleagues’ hard work – years spent writing and revising the curricula that we would now publicly label inadequate and problematic. Moreover, the vast majority of our audience had taught, led, and built their careers in the very instructional paradigms we would now disavow.

We did not want to hurt or offend. But we also believed deeply – very deeply – in our message, and in the need for change. We planned exhaustively, right up to the end – even skipping a traditional karaoke contest the night before. After lunch, we took our clickers and microphones, and the session began. We asked our colleagues to reflect on these words:

| “Liberating education exists in acts of cognition, not transferals of information” –Paulo Freire |

We hoped for openness and enthusiasm; we feared anger and defense. We got all of that, and everything in between.

A Timely Reading

Back on my couch the next morning, my mind continued to race. I had expected the session to provoke a range of responses, but I had not expected the feeling of that conference room. It had been charged, tense, anguished. The idea of shifting pedagogy was very hard for our adult community to hold. Whether voicing gratitude, hope, skepticism, or fear, participants engaged the session from an intensely personal and emotional place. I struggled to make sense of what had happened during those two hours – as a facilitator, as an educator, and as a person.

Unable to shake the confusion, and feeling a bit lost, I decided to read. If I could not understand what had happened during the session, I could at least deepen my own understanding of progressive instruction. So, I tore into Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970) and hooks’ Teaching to Transgress (1994)with abandon.

Reading both texts in succession proved a tremendous experience. The books spoke to, and complicated, my own emerging ideas and values about schooling. They invited reflection on my past teaching and leadership; they demanded action for my future work. They were unapologetic, critical, loving, optimistic. I left them feeling challenged and inspired.

As I read Freire and hooks, I found myself thinking about a graduate course I had taken five years prior: School Leadership for Adult Development. Taught by the stellar Eleanor Drago-Severson,this course investigated best practices for leading schools in ways supportive of not only student learning, but also adult growth. The course’s guiding theoretical framework was constructive-developmental theory (Kegan, 1982; see also Kegan & Lahey, 1984). This theory offers a comprehensive view of how adults think about themselves, and about the broader world, at various stages of their personal development. Kegan’s theory continued to rise to the fore of my consciousness as I read Freire and hooks. I found so much of their language, and so many of their ideas, to be resonant with the constructive-developmental framework. I also began to develop some new insights – albeit nascent and untested – as to why our Great Teaching session had become so fraught.

This paper is an attempt to share some of my developing thinking about the relationship between adult development theory and critical pedagogy. In the following section, I offer an overview of Kegan’s constructive-developmental framework. From there, I build on my aforementioned, informal noticings of Pedagogy of the Oppressed and Teaching to Transgress, performing a formal close reading of both texts through a constructive-developmental lens.

Section Two: An Overview of Constructive-Developmental Theory

There are a number of excellent articulations of constructive-developmental theory. In addition to Kegan’s (1982) pioneering text, I find his later articles (see Kegan & Lahey, 1984; Kegan, 2000) and various works by Drago-Severson (2004, 2009) to be useful. Though I am far from expert on the topic, I draw from the above sources to offer an overview of Kegan’s constructive-developmental framework. Given my specific interest in the theory’s relationship to pedagogy, I will use the role/character of “teacher” to provide illustrative examples.

Constructive-developmental theory posits that an adult’s subject-object relationships provide a valuable lens for understanding how they make meaning of the world. An individual is subject to those things about which they lack awareness; from which they cannot separate the “I,” or the self. By contrast, an individual can hold as object those things that they can understand as separate from the self. Because these objects are not one with the self, the individual can reflect upon them. The constructive-developmental view suggests that eanin

The Instrumental Knower

In the instrumental stage, adults are subject to their needs and wants. They can hold as object their impulses, but they are unable to reflect upon or critique their desires. Adults at this stage thus make sense of the world in a self-serving way, interpreting things as “good” if they serve desires and “bad” if they do not. Instrumental knowers often take a concrete, rules-based approach to their work. For example, an instrumental knower who wants to become a “good” teacher will seek specific and objective criteria for “good” teaching. They will work to satisfy those criteria and will experience themselves to be a “good” teacher once the criteria are met. An instrumental teacher likely finds meaning, for example, in clear performance rubrics.

The Socializing Knower

Should an adult develop past the instrumental stage, they enter the socializing stage. Here, the individual can (newly) hold as object their needs and desires; they now have the capacity to understand and critique desire as separate from the self. The adult becomes subject to their relationships. Their self-concept is dependent upon theirview of how others view them. Said otherwise, they make meaning through relationships. A socializing knower who seeks to become a “good teacher” finds meaning in the opinions of other people. Feedback from others –

positive or critical – is the primary means by which this person understands the quality of their teaching. For the socializing teacher, clear performance rubrics mean little unless paired with a colleague’s praise or critique.

The Self-Authoring Knower

When an adult develops the capacity to hold their relationships as objects, they enter the self-authoring stage. At this stage, the individual can reflect upon and critique their relationships. They no longer make sense of the world primarily through the eyes of others. Instead, the adult is subject to a (growing) set of self-defined values. Their values, rather than their relationships, shape their worldview. A self-authoring teacher considers themselves to be “good” if they view their practice to be aligned to their values. Rather than look to objective criteria or seek the approval of others, this teacher asks: does the way I teach align to my view of great teaching? Am I accomplishing what I believe great teachers accomplish? This teacher may find objective rubrics or peer/manager feedback helpful – but only if they operate in alignment with the teacher’s own values.

The Self-Transforming Knower

The large majority of adults are instrumental, socializing, or self-authoring. There is, however, a fourth stage: self-transforming. At this stage, an adult develops the capacity hold their own values as object. Here, the individual is increasingly aware of how their values are contextualized within broader social, cultural, biographical, and political systems (to name a few). They can critique and reflect upon the “authorship” of their identity. They no longer understand the world primarily through their own values; instead, they make meaning of the world as a set of interrelated systems. They are now subject to the concept of interconnectivity. A self-transforming teacher understands their view of “good” teaching as resulting from various dynamic and evolving interrelated systems. For example, this teacher may locate their value of “building relationships with students” in their study of a rubric, in the feedback of a mentor teacher, and in their own lived classroom experiences. They may even reflect on how race, class, and faith have contributed to their understanding of what characterizes a “good” student-teacher relationship.

Figure 1:

Constructive-Developmental Ways of Knowing

| Subject (“I”; unable to view as distinct from self) | Object (able to reflect upon as distinct from self) | Meaning-Making at this stage | How a teacher at this stage might assess their efficacy | |

| Instrumental | Needs and Wants | Impulses | Dependence on rules | Scoring proficient on a teaching rubric |

| Socializing | Relationships | Needs and Wants | Dependence on affirmation and affiliation | Receiving positive feedback from peers |

| Self- Authoring | Values | Relationships | Reliance on self-generated values and standards | Achieving outcomes aligned with their own view of good teaching |

| Self- Transforming | Inter- connected Systems | Values | Self-exploring; seeks input from others to further develop/change worldview | Reflecting on the self’s concept of “good” teaching by inviting thoughts, dialogue, and conflict with others. |

Note. Based on similar tables in Drago-Severson (2004, Table 2.1; 2009, Table 2.1).

Section 3: Intersubjectivity and Self-Transformation in Pedagogy of the Oppressed

In Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970), Freire constructs his framework for a liberatory pedagogy through the lens of subject / object relationships. He defines this pedagogy as one

…which must be forged with, not for, the oppressed (whether individuals or peoples) in the incessant struggle to regain their humanity. This pedagogy makes oppression and its causes objects of reflection by the oppressed, and from that reflection will come their necessary engagement in the struggle for their liberation. (p. 48)

In Freire’s model, the oppressed are initially subject to the condition of oppression: “…their perception of themselves as oppressed is impaired by their submersion in the reality of oppression” (p. 45). One outcome of liberatory pedagogy, then, is a renegotiation of the oppressed’s worldview, such that the oppressed can hold as object what was once subject. Through liberatory education, the oppressed can come to recognize, reflect, and act upon their oppression in way that they previously could not.

Intersubjectivity thus figures prominently in Freire’s description of liberatory pedagogy. Take, for example, Freire’s assertion that critical pedagogy “must be forged with, not for the oppressed.” The emphasis is Freire’s, not my own. His stressed conjunctions signal the importance of teachers and students coexisting as subjects, rather than in a subject/object dichotomy. As in constructive-developmental theory, the result of intersubjectivity is ongoing transformation: “And in the struggle this pedagogy will be made and remade” (p. 48).

As Freire elaborates, the centrality of intersubjectivity to his pedagogy becomes even more apparent. He writes, for example, that “…one cannot conceive of objectivity without subjectivity. Neither can exist without the other, nor can they be dichotomized…subjectivity and objectivity [are] in constant dialectical relationship” (p. 50). He closes his first chapter by imagining how teachers and students might embody this dialectical relationship:

A revolutionary leadership must accordingly practice co-intentional education. Teachers and students (leadership and people), co-intent on reality, are both Subjects, not only in the task of unveiling that reality, and thereby coming to know it critically, but in the task of re-creating that knowledge. As they attain knowledge of reality through common reflection and action, they discover themselves as its permanent re-creators. (p. 69)

Note, again, Freire’s yoking of intersubjectivity and transformation. It is co-intentionality and mutual subjectivity that lead to re-creation.

In his second chapter, Freire contrasts this intersubjective teacher-student framework to the “banking” model of education, wherein “knowledge is a gift bestowed by those who consider themselves knowledgeable upon those whom they consider to know nothing” (p. 72). He concludes his list of banking-model descriptors with this conceptual summary: “the teacher is the Subject of the learning process, while the pupils are mere objects” (p. 73). For Freire, this dichotomous subject-object classroom cannot be liberatory. Instead, students and teachers must coexist as subjects. They must work together to understand and critique their own worldviews –

to “unveil” their realities – and then to co-construct new ones. In this way, their coexistence both requires and permits transformation. Freire charges educators to resolve the “teacher-student contradiction” by creating a new framework of “teacher-students with students-teachers.” Here, Freire’s hyphenation and chiasmic structure amplify the intersubjective condition.

Freire continues with what I find to be an especially clear (and moving) articulation of his vision for liberatory education:

The teacher is no longer merely the-one-who-teaches, but one who is himself taught in dialogue with the students, who in turn while being taught also teach. They become jointly responsible for a process in which all grow…here, no one teaches another, nor is anyone self-taught. People teach each other, mediated by the world, by the cognizable objects which in banking education are ‘owned’ by the teacher. (p. 80)

The relatedness of intersubjectivity (“jointly responsible”; “teach each other”) and self-transformation (“all grow”) in Freire’s framework is striking; it is precisely what constructive-developmental theory predicts. At the self-transforming stage, the individual is in a constant process of identity formation and re-formation, because they can critique not only their own values, but also the very idea of self-authorship. Freire presents identity negotiation as a natural consequence of learning spaces in which teachers consider their students to be co-subjects, rather than objects: “Problem-posing education affirms men and women as beings in the process of becoming – as unfinished, uncompleted beings in and with a likewise unfinished reality…they are aware of their incompletion” (p. 84). The phrase “aware of their incompletion”is highly resonant with Kegan’s conception of the self-transformer.

Dialogue is key to Freire’s liberatory, transformative pedagogy. It must, however, be a particular dialogue. It “cannot exist without humility” and must describe a “horizontal relationship”; teachers must view students as fellow subjects (other “Is”), rather than objects (“its”). In describing the conditions necessary for such dialogue, Freire resurfaces the language of transformation. To dialogue, individuals must have “faith in their power to make and re-make, to create and re-create,” and must further possess a “hope [sic] rooted in men’s incompletion” (pp. 90-91).

Constructive-developmental theorists suggest that Freire’s humble, horizontal, and transformative dialogue is available at the self-transforming stage. Drago-Severson (2004) lists the following as core “guiding questions” of an intersubjective knower:

- How can other people’s thinking help me to enhance my own?

- How can I seek out information and opinions from others to help me modify my own ways of understanding?

Drago-Severson further describes the self-transformer’s attitude toward conflict as “basic to life” and an “[opportunity] to enhance thinking” (pp. 26-27). It follows that self-transforming teachers are best situated to dialogue in a Freirean mode.

Freire also takes care to warn against the dangers of dogmatic pedagogues. Whereas a true radical operates such that “subjectivity and objectivity [sic] join in a dialectical unity” (intersubjectivity), a failed radical is one who “falls into essentially fatalistic position” and “[closes] themselves into ‘circles of certainty’ from which they cannot escape.” These failed radicals, he writes, “make their own truth” (pp. 38-39). This phrase is resonant with Kegan’s self-authoring knower, who is subject to their own self-determined values. Self-authoring individuals are not necessarily “fatalistic.” Still, it is relevant that Freire contrasts a leader/teacher who can co-construct knowledge with one limited by (subject to) his/her own beliefs. Freire’s liberatory pedagogue is not only explicitly self-transforming; they are also explicitly not self-authoring. As in constructive-developmental theory, these two stages are distinct.

All told, my constructive-developmental reading of Freire suggests that he imagines critical pedagogues to be self-transforming, as they must have the capacity to build genuinely intersubjective spaces. If teachers cannot view students through an intersubjective lens – if they lack awareness of their own incompletion – then they cannot teach to liberate. Problem-posing education “…requires that the Subject recognize himself in the object … and recognize the object as a situation in which he finds himself, together with other Subjects” (p. 105). Adopting the voice of a radical pedagogue, Freire says “I cannot think for others or without others, nor can others think for me.” This language makes clear that Freire’s educator must be able self-transform. They must have capacity for intersubjective meaning-making.In footnote 10, Freireexplicitly uses the term “intersubjectivity” to define a “theory of revolutionary action” (p. 108).

This idea that critical pedagogy requires self-transforming capacity is significant for those of us who aspire to teach progressively, if not radically. According to constructive-developmental theory, individuals attain transforming capacities only after a substantial amount of developmental growth, having moved through the instrumental, socializing, and self-authoring stages. Recall that such growth is not “guaranteed.” Adults experience developmental growth not as a natural consequence of age or life phase, but rather if (and only if) engendered by their unique lived experiences. Indeed, research in constructive-developmental theory indicates that very few (less than three percent) of the U.S. adult population are self-transforming. The majority, in fact, make meaning two stages prior, as socializers (see Drago-Severson, 2009, Figure 2.2).

Freire does not suggest that developmental growth or capacity is requisite for the liberatory pedagogue. He argues for what educators must do and not do; how they must think and not think. But one leaves Pedagogy of the Oppressed with the sense that they can (and should) start tomorrow. There is no suggestion that a developmental process must first take place. I lodge this not as a criticism, but rather to highlight the way in which a constructive-developmental reading furthers and deepens our understanding of critical pedagogy in action.

Indeed, reading Freire through the constructive-developmental lens helped me to better make sense of our fraught Great Teaching session. Following this close reading, I naturally recalled the room of adults; the way it had become so tense and uncomfortable. I thought, too, about a conference I had attended six months prior, where a team of high school instructional coaches had commiserated over the staunch persistence of direct instruction in their classrooms. I thought about my own work over the past year; about trainings in which teachers had voiced enthusiasm for maximizing discourse, but who had resorted to old teacher-centric habits by the time I observed them just weeks later.

A constructive-developmental lens helps us to understand why it can be so hard to implement critical pedagogy at scale. Freire provides the vision of an intersubjective classroom; Kegan explains that such intersubjectivity is hard to achieve. Intersubjective knowing demands self-transforming capacity, which comes with a lot of developmental growth. Odds are, the aspiring liberatory pedagogue is not ready. At least, not yet.

Section 4: Intersubjectivity and Self-Transformation in Teaching to Transgress

As my curiosity regarding the interplay between critical pedagogy and adult development grew, I felt compelled to perform a second constructive-developmental close reading. For this, I revisited bell hooks’ Teaching to Transgress (1994). In this collection of essays, hooks reflects on her journey in becoming a critical pedagogue, citing Freire as a profound influence. Throughout, she makes sense of her teaching as intersubjective while demonstrating her own self-transforming capacity. hooks’ introduction, in which she discusses her pedagogic influences, is illustrative:

When I discovered the work of Brazilian thinker Paulo Freire, my first introduction to

critical pedagogy, I found a mentor and a guide, someone who understood that learning could be liberatory. With his teachings and my growing understanding of the ways in which the education I had received in all-black Southern schools had been empowering, I began to develop a blueprint for my own pedagogical practice. Already deeply engaged in feminist thinking, I had no difficulty bringing that critique to Freire’s work. Significantly, I felt that this mentor and guide, whom I had never seen in the flesh, would encourage and support my challenge to his ideas if he was truly committed to education as the practice of freedom. At the same time, I used his pedagogical paradigms to critique the limitations of feminist classrooms. (p. 6)

Here, hooks displays a keen awareness of how influential mentors (Freire), past experiences (attending all-black schools in the South), and theories (feminism) intersect in her biographical and pedagogical sense-making. Note how hooks’ language positions these influences in active dialogue. Freire meets a “growing understanding” of hooks’ primary schooling; feminism “[brings] critique” to Freire; hooks freely imagines Freire’s response. Her confident, plain narration belies an intersubjective worldview that gives rise to personal transformation; hooks’ personal and pedagogic values evolve in the context of her dynamic meaning-making systems.

The structure of hooks’ writing also reveals her intersubjective and self-transformative capacities. Recall that discourse and exchange are central to meaning-making at the self-transforming stage. It is telling, then, that hooks writes two of her essays entirely in dialogue. Especially noteworthy is her essay on Freire. She writes the piece as a “playful dialogue with myself, Gloria Watkins, talking with bell hooks, my writing voice” (p. 45). Here, hooks’ innovative form – the imagining of two “selves,” who then discourse about a theorist and his influence upon her/their lives – reveals that she can view her “self” as a subject-object, interconnected with other subject-objects; and that she can see and analyze her evolution of self.

hooks’ discussion of her teaching practices further reflects intersubjectivity and self-transformation. She notes in her introduction that “any radical pedagogy must insist that everyone’s presence is acknowledged…there must be an ongoing recognition that everyone influences the classroom dynamic, that everyone contributes” (p. 8). As a result of this mutuality, the classroom is an evolving environment in which meaning is co-constructed: “When the classroom is truly engaged, it’s dynamic. It’s fluid. It’s always changing. Last semester, I had a…great class. The students left realizing that they didn’t have to think like me, that I wasn’t there to reproduce myself” (p. 158). Here, hooks’ language is particularly reminiscent of self-transformation. She has the capacity to understand the “self” as object. She has an aversion to “reproducing” herself when she teaches, aspiring instead toward co-constructed knowledge.

Later on, hooks more directly defines her classrooms as intersubjective. Like Freire, she valorizes dialogue, describing it as “one of the simplest ways we can begin as teachers, scholars, and critical thinkers to cross boundaries, the barriers that may or may not be erected by race, gender, class, professional standing, and a host of other differences” (p. 130). hooks is aware of how these identity markers are mutable and interrelated. Her language of crossing boundaries and dismantling barriers underscores an intersubjective view. The very title of her essay collection – Teaching to Transgress – does the same.

At the end of her dialogic essay “Building a Teaching Community,” hooks offers this striking summary of her pedagogy: “We have a lot of people who don’t recognize that being a teacher is being with people” (p. 165). These are powerful phrases which yoke intersubjectivity with self-transformation. Her conjunctions are telling: teachers must be with students as co-creators of knowledge; they also must be, in their very orientation, with and not for people.

Why don’t we have a lot of people who view being a teacher as being with people? Developmental stage may have something to do with it. hooks’ essays suggest that she can teach critically not only because she has a vision for intersubjective classrooms, but also because she has the developmental capacity to know the world intersubjectively. As a self-transforming knower, she can truly view herself as interconnected with her students. Indeed, self-transforming capacity may make the difference. It is one thing to make space for dialogue; it is another to genuinely view students as co-constructors of knowledge through dialogue. hooks articulates this difference when she reflects on her colleagues in academia: “Professors, even those who view themselves as liberal, may think that it’s good for students to speak, only to proceed in a manner that devalues what the students stay” (p. 149).

As hooks meditates further, she positions her developmental capacity as a key driver of her liberatory practice. hooks recalls her early undergraduate days and critiques her professors’ lack of attention to personal growth: “…I was certain that the task for those of us who chose this vocation was to be holistically questing for self-actualization” (pp. 16-17). In the academy, hooks found teachers preoccupied with “book knowledge” rather than teachers in pursuit of self-betterment. She laments their disturbing “dualistic separation” of the teacher (as person) from their craft:

The self was presumably emptied out the moment the threshold was crossed…there was fear that the conditions of that self would interfere in the teaching process. Not surprisingly, professors who are not concerned with inner well-being are the most threatened by the demand on the part of students for liberatory education, for pedagogical processes that will aid them in their own struggle for self-actualization. (pp. 16-17)

In hooks’ intersubjective view, a teacher should critique and negotiate the self as part of their liberatory pedagogy. She borrows language from Maslow’s hierarchy (self-actualization), but we can readily adopt a developmental lens. To hooks, the progressive educator must have a commitment to – and by extension, the capacity for – self-transformation.

Indeed, hooks feels that her ability to abdicate the “self” distinguishes her from pseudo-progressive colleagues. hooks writes that she has “benefited a lot from not being attached to myself as an academic or professor,” whereas her colleagues have been limited by a fixed sense of self: “I feel that one of the things blocking a lot of professors from interrogating their own pedagogical practices is that fear that ‘this is my identity and I can’t question that identity’” (pp. 134-135). This contrast can be viewed as a difference in developmental stage. hooks has a fluid view of the “self,” characteristic of the self-transforming stage; her colleagues have a static view of self, characteristic of the self-authoring stage. hooks goes on to argue that “by recognizing subjectivity and the limits of identity, we disrupt that objectification that is so necessary in a culture of domination” (pp. 139). An ability to critique subjectivity and identity differentiates the self-transforming and self-authoring stages. Thus, in hooks’ view, it is the self-transforming teacher who can successfully dismantle oppressive paradigms and teach to liberate.

If self-authoring knowers cannot fully teach to liberate, it follows that socializing knowers will also fall short. hooks observes this, noting that “the urge to experiment with pedagogical practices may not be welcomed by students who often expect us to teach in a manner they are accustomed to,” and that academics’ “negative critique of progressive pedagogy makes teachers afraid to change” (pp. 142-143). A socializing knower, who makes meaning through others’ opinions, would likely respond to such critiques by resorting to more familiar and widely approved methods. It is, then, the socializing teacher’s developmental capacity which drives their retreat from more radical techniques.

In hooks, we find a critical pedagogue whose practices result from (1) her deep understanding of liberatory pedagogy (via her study of Freire) and (2) her developmental capacity to make meaning intersubjectively. To teach like hooks, then, we must not merely study, name, and emulate critical practices. We must also develop her self-transforming way of knowing.

Studies of constructive-developmental theory suggest that few of us are prepared to teach like hooks. As mentioned earlier, only a small fraction of the adult population are self-transforming knowers. This fact illuminates the scope of the challenge facing aspiring critical educators. Still, I left Teaching to Transgress with abundant optimism. hooks’ intersubjectivity evolved with time – and her journey, while inspiring, need not be unique. In fact, it proceeds just as Kegan would predict.

When hooks describes her early teaching career, she reveals her acute socializing tendencies. hooks recalls the moment she was offered tenure at Oberlin College: “Instead of feeling elated when I received tenure, I fell into a deep, life-threatening depression. Since everyone around me believed that I should be relieved, thrilled, proud, I felt ‘guilty’ about my ‘real’ feelings and could not share them with anyone” (p. 1). Hooks struggled to accept her own perspectives on tenure because she was very aware of – and at least somewhat subject to – others’ beliefs.

Having studied Freire as an undergraduate, hooks attempted critical practices from the start of her teaching career (p. 14). Initially, hooks struggled to upkeep her progressive agenda, largely because her students disapproved of her methods:

…I found that there was much more tension in the diverse classroom setting where the philosophy of teaching is rooted in critical pedagogy and (in my case) in feminist critical pedagogy. The presence of tension – and at times even conflict – often meant that the students did not enjoy my classes or love me, their professor, as I secretly wanted them to do. (p. 42)

In this final phrase, hooks confesses her socializing worldview. Though she is aware of and committed to critical pedagogy, she longs for others’ affirmation.

Later, hooks discusses how she now makes meaning of student critique:

Students do not always enjoy studying with me. Often they find my courses challenge them in ways that are deeply unsettling. This was particularly disturbing to me at the beginning of my teaching career because I wanted to be liked and admired. It took time and experience for me to understand that the rewards of engaged pedagogy might not emerge during a course. (p. 206)

Again, hooks plainly confesses her former socializing perspective; she “wanted to be liked and admired.” But she has certainly grown. Her first sentence is declarative and unapologetic. Now, hooks is entirely comfortable with the idea that others may not love her teaching style. This growth, she notes, has come with “time and experience.”

She narrates the growth process at greater length in “Building a Teaching Community”:

Another difficulty I had to work through early on as a professor was evaluating whether or not our experience in the classroom had been rewarding. In the classes I teach, students are often presented with new paradigms and are being asked to shift their ways of thinking to consider new perspectives. In the past I have often felt that this type of learning process is very hard; it’s painful and troubling…that was really hard for me, because I think part of what the banking system does for professors is create the system where we want to feel by the end of the semester every student will be sitting there filling out their evaluations testifying that I’m a ‘good teacher.’ It’s about feeling good, feeling good about me, and feeling good about the class. But in reconceptualizing engaged pedagogy I had to realize that our purpose here isn’t really to feel good…we have to learn how to appreciate difficulty, too, as a stage in intellectual development (pp. 153-154).

hooks vividly remembers how hard it was for her prior self to hold critical feedback. However, she then speaks to the inadequacy of “good feeling” as a measure of good teaching. Here, we see evidence of hooks’ developmental growth. hooks discusses her socializing tendencies in the past tense. She can clearly hold her relational worldview as object.

hooks is also self-aware of her personal growth. She mentions her “learning process,” noting that she had to reconsider her purpose as a teacher, and to “learn how to appreciate difficulty.” Significantly, hooks views her developmental growth as instrumental to her ongoing implementation of critical practices. It is “in reconceptualizing engaged pedagogy” that hooks finds capacity to reimagine her goals as an educator and to work past (or grow past) her socializing need for approval.

In this way, hooks’ awareness of and commitment to Freire’s ideas became a site for her developmental growth. It is important to note that hooks’ self-transforming capacity did not precede her attempt at liberatory pedagogy. As she tried to teach critically, she grew – not only in her educational practice, but also in her developmental stage.

My conclusions here are inferential, and admittedly limited by my methodology (a focused close reading of select essays). Still, there seems to be value in the working idea that an educator’s vision for and continued attempts at critical pedagogy can simultaneously require and engender developmental growth. I see this in Teaching to Transgress. I suggest that hooks’ study of Freire, and her desire to implement critical methods, gave rise to a set self-authored values (intersubjectivity, critical pedagogy). Gaining clarity on her values helped hooks to move past the socializing stage. Then, with time, as hooks experimented with critical techniques, her authoring capacity evolved. The more hooks worked to build intersubjective classrooms, the more she grew her own capacity to know intersubjectively. In her journey to teach critically, she found the very developmental capacity she needed.

Section 5: Potential Implications

The ideas surfaced from my close readings may prove valuable for aspiring critical educators. First, raising practitioners’ awareness of the relationship between adult developmental capacity and critical methodology may have a productive influence on professional learning plans. Imagine a teacher who has studied Freire, hooks, and other critical pedagogues. Through this study, the teacher has developed a theoretical understanding of intersubjective classrooms, along with a genuine thirst to build them. Encouraging this teacher to additionally study constructive-developmental theory – to consider intersubjectivity not just as an external pedagogical state, but also as an internal, developmental one – may valuably expand their learning agenda. Benefiting from their study of both pedagogy and development, they now work to pursue both a pedagogical and developmental learning plan.

Such awareness will also benefit the work of education leaders who aspire to cultivate critical practices in their teachers and learning communities. Leaders who consider the interplay of critical pedagogy and adult development will more likely view their roles as not only evolving teacher practice, but also as evolving teachers’ ways of knowing. A concern for progressive educators’ developmental needs will direct coaches toward a rich and growing body of research supporting the application of constructive-developmental theory to school leadership. Drago-Severson (2004, 2009), for example, proposes four pillar practices that school leaders can implement to cultivate educators’ developmental capacity. These practices are teaming, leadership roles, mentoring, and collegial inquiry. Because these practices have been found to support adult growth, educators might consider specifically deploying them when looking to shift teacher practice toward more critical instructional methods.

Teams of educators, too, might evolve their work together with a heightened awareness of developmental capacity. Imagine a teaching team that has studied critical pedagogy. They agree that elevating student-centered discourse is an important next step for their department. The teachers also understand that critical pedagogy calls for discourse to be intersubjective. They further understand that goal of intersubjectivity places significant developmental demands on each one of them. Having studied constructive-developmental theory, they acknowledge that members of the team are not equally prepared for this pedagogical project. They might next ask: As we strive to build more discourse-centered classrooms, how do our ways of knowing influence our professional needs? How can we best support one another – developmentally – as we do this work?

Table 2 is an illustrative example of the thinking that might result when an individual, coach, or team explores these questions through a developmental lens:

Table 2: Possible Perspectives of Student Discourse Across Developmental Stage

| Way of Knowing | What support might this teacher need? | What challenges might this teacher face? | What can this teacher contribute? |

| Instrumental S: Needs, Wants O: Impulses | Clear rules / expectations / tactics for implementing discourse. | Lack of clear goals / outcomes / metrics for an “effective” discourse. | Insight as to which concrete resources / tactics are more and less helpful for implementing discourse. |

| Socializing S: Relationships O: Needs, Wants | Affirmation from coaches and colleagues when implementing effective discourse practices. | Students may experience pedagogy shift as unclear or unpleasant and share critical feedback. | Insight and advice as to how students and other constituents are experiencing the pedagogical shift to discourse. |

| Authoring S: Values O: Relationships | Space to capture and share their developing thoughts on effective discourse. | Inviting students to contribute may challenge and test strongly held values (both about teaching and about course content). | Rally/center team and constituents around clear values and commitments for discourse. |

| Transforming S: Interconnected Systems O: Values | Space to chart and reflect upon their evolving values and sense of self as they engage in discourse with students. | Holding the experience of shifting/evolving self with professional and personal demands. | Elevate team awareness around how interconnected variables are influencing the ways in which students and adults draw meaning from discourse; model an intersubjective relationship with students. |

For now, these are hypothetical and untested ideas for how educators might construct and engage in simultaneous pedagogical and developmental learning. Further research is required to better understand the precise relationship between critical pedagogy and adult development, along with the developmental practices that can best support aspiring critical educators.

But, for my own work, peering through the developmental lens has already gifted me with greater clarity. Constructive-developmental theory explains, at least in part, why I have found it so challenging to lead adults in implementing student-centered pedagogies. Until now, I have not considered that I may be asking practitioners to stretch both as educators and as humans – to not only teach differently, but to know differently. And now, when I think back to that Great Teaching session, I better understand the tense and heavy feeling of the room. I think that feeling was the result of many adults, at many different stages, struggling to make sense of intersubjectivity – a concept that challenges the very ways in which they understand not only their classrooms, but the world.

In some ways, the clarity is intimidating. To reform teaching practice, I must not only investigate and implement progressive techniques; I must also tend to my developmental growth. I must lead others in tending to their growth, and to the growth of the practitioners in our care.

Yet, despite the weight of this charge, I find myself more excited than scared. There are places to start. The work of Kegan, Drago-Severson, and others provides practical, research-based guidance on fostering adult development in schools.

I have, too, the rich experience of reading hooks. Hers is a success story; a narrative of how one teacher’s quest for a liberatory pedagogy served as the very site of her personal growth. Her awareness of and commitment to intersubjectivity became her capacity to self-transform. If we share hooks’ awareness and commitment, it follows that we, too, can grow and teach like her. She reminds us, after all, that the critical educator’s “pedagogical strategies…may be not just for our students but for ourselves” (p. 134).

References

Drago-Severson, E. (2004). Helping teachers learn. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press.

Drago-Severson, E. (2009). Leading adult learning: Supporting adult development in our schools. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York: Routledge.

Kegan, R. (1982). The evolving self. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Kegan, R. & Lahey L.L. (1984). Adult leadership and adult development: a constructionist view. In Kellerman, Barbara (Ed.). Leadership: Multidisciplinary Perspectives.

Kegan, R. (2000). What “form” transforms? A constructive-developmental approach to transformative learning. In J. Mezirow & Associates (Eds.), Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress (pp. 35-69). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Maxwell, J.A. (2008). Designing a qualitative study. The SAGE handbook of applied social science research methods, 2, 214-253.

Reason, P. (1988). Introduction. In P. Reason (Ed.), Human inquiry in action: Developments in new paradigm research (pp. 1-17). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.