In my younger years, I was a cartoonist. Every night, after dinner, I would sharpen a few pencils and grab a stack of long, 8×14 paper that my mother brought home from work. I’d lie down on my belly in front of the TV, pencils to the left, paper in front of me, and draw the night away. I drew familiar characters in imagined scenes: Batman and Mr. Freeze battling on Gotham skyscrapers, Archie and Veronica at a school dance, Data and Captain Picard on the Enterprise bridge. Disney characters surged each summer, when their new movies dropped. I developed a few characters of my own, too. I was a little cartoon factory, churning out three to five legal-size compositions a night.

Before we continue: This essay will reference, unapologetically, the cartoons and characters of my 90s childhood, specifically, the era just before the rise of Spongebob. It is my staunch and biased belief that cartoons have never been as good as since. In TV, we’re talking Rugrats, Doug, Ren & Stimpy, Batman: The Animated Series, Hey Arnold!, and Tiny Toons. In film, we’re talking a Disney golden era: the series of summer blockbusters that started with The Little Mermaid and ended somewhere around Mulan, depending on who you ask. You might think I’m an old geezer, and surely you have your own list of cherished childhood cartoons. But I stand by my list, and I’m forever grateful that I was a kid when I was a kid!

In any case, back then, cartooning was like breathing for me. Mostly, I drew for myself; but sometimes, my friends asked me for pictures. They wanted Jasmine and Aladdin on the magic carpet, or generically cute puppies, or racecars. I enjoyed these commissions. They provided immediate inspiration and clear direction, and when I returned the next morning and delivered the custom drawings, I was rewarded with plenty of gratitude and praise.

In fourth grade, I found a unique opportunity to formalize – and to profit from – my cartoons. My teacher, Mr. B, announced one morning that we would be launching a classroom economy. We would each get bank accounts and checkbooks. We would earn salaries for our classroom jobs, with bonuses available for one-off tasks. We could use our earnings to purchase various incentives: extra recess time or special lunches or trips down the hall to see old favorite teachers. Mr. B had a special gift for us that morning: a kick-off deposit of $100. He walked from desk to desk, handing out various combinations of Monopoly money – five green twenties, two purple fifties, or a single, crisp, pale hundred-dollar bill. We applauded and ooooed and aweeed.

In addition to our salaries, Mr. B encouraged us to think about other ways to become savvy earners. “For example,” he said, “my previous classes have used snack time to set up their own shops.”

Very intriguing.

“Where?” asked a classmate.

“Right here,” said Mr. B, gesturing to the small tables where he kept stacks of worksheets.

“What kind of shops?” asked another.

“Ah, that’s for you to decide,” he said with a faint, knowing grin.

“Can we sell anything?”

He laughed. “No, not anything. But most things. I’ll let you know if any of your products are out of line. And you can ask me about your ideas before you open, if you like.”

“Who sets the prices?”

“You. You set the prices.”

We looked at one another, smiling and nodding. Such power!

“And now,” Mr. B said, “it’s snack time.”

We unzipped our lunchboxes, pulled out various baggies of pretzels and teddy grahams and cheddar goldfish, then huddled in our various friend groups. Snack time was, of course, the highlight of the day. So much so that I still remember its precise start time: 10:20am.

That morning, my friends and I discussed the new classroom economy: how we intended to spend our money, what strategies we would use to procure the bonus tasks, and whether or not we would open snack-time shops.

I had been mulling the shop opportunity since Mr. B had mentioned it. I certainly wanted to run one. And when it came to the product – well, that seemed obvious. I was already known for my cartooning, and I had been giving away the goods for free! Maybe it was time to cash in.

“I’m going to open an art gallery,” I said. “And sell my drawings.”

My friends approved. “Great idea!”s all around. We briefly discussed which characters we thought would sell best. Rugrats and Toy Story, very hot. Tiny Toons, reliable. Captain Planet, hit or miss. For superhero fans, Batman and X-men were good bets.

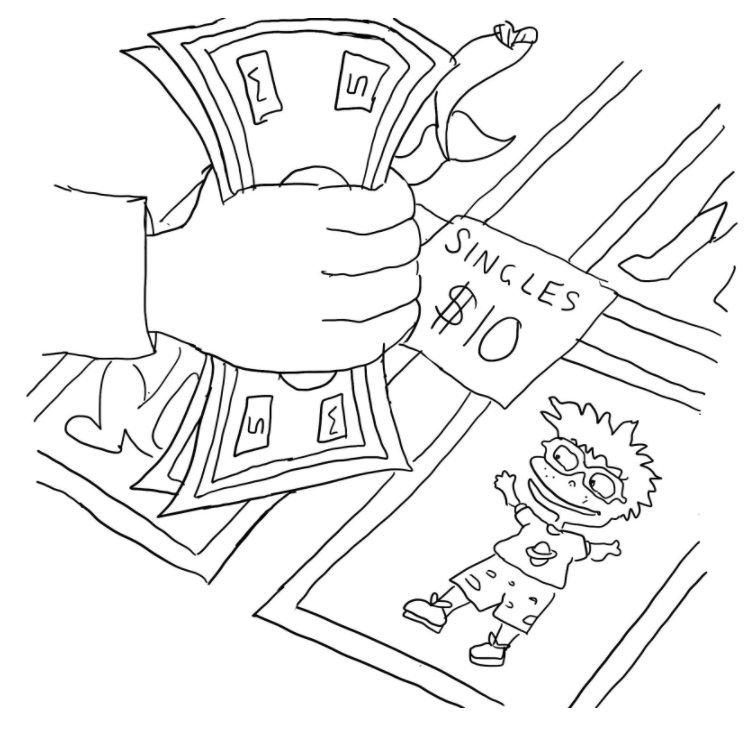

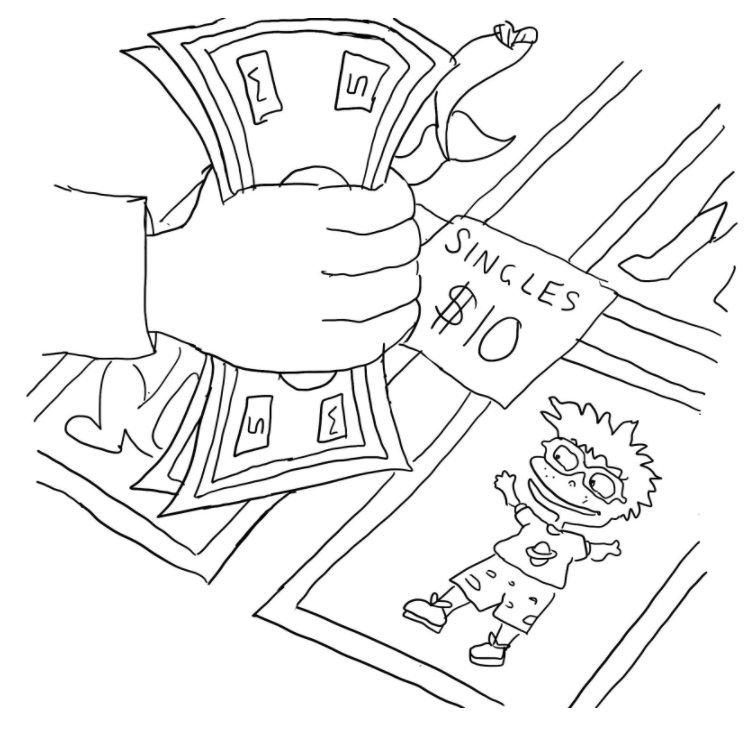

I spent the rest of the day planning for my gallery. I jotted character names in the margins of my composition notebook, alongside long division problems and grammar exercises. For each character, I estimated how many pieces I would draw and how much I would charge. I thought through a few bigger pieces to feature – a full-cast portrait of the Rugrats, a side-by-side of Woody and Buzz. My goal was to open with no fewer than 30 items. I also thought through a custom pricing scheme: $10 for a single character, $15 for two together, $20 for three. $25 for a commissioned piece. I had a sense of how such deals worked, based on TV commercials and grocery store aisles.

Once at daycare, I powered through my homework and got straight to work. For single-character portraits, I chose index cards – small, sturdy, and easy to carry. For the feature scenes, I worked with full-size construction paper. I was determined and confident. Years of nightly, TV-adjacent sketching had prepared me well. I had already completed half the collection by the time my mother picked me up. After a hurried dinner of Ellio’s Pizza, I assumed my familiar post on the living room floor, and I finished the rest of the drawings. As my final task, I took a clean sheet of legal paper and wrote Andy’s Art Gallery in big graffiti letters, then listed the pricing scheme beneath. Just as I was about to turn in, a final idea struck. I added to the upper right corner: GRAND OPENING! SPECIAL OFFER! Buy two, get one free!

Satisfied, I clipped the cap back on the Crayola marker and shoved my art supplies under the coffee table. I would clean up tomorrow. I took all my drawings, brought them into the kitchen, and secured them in my backpack. I went to bed, tired yet restless, anticipating the opening of my gallery at 10:20 the next morning.

***

When Mr. B announced snack time, I rushed over to the tables that he had set aside for our shops. Hye-jin, my best friend again, had agreed to help me set up. We arranged the larger feature pieces down the center of the table, then surrounded them with the smaller index-card portraits. With a long piece of Scotch tape, I affixed the shop name and pricing scheme to the ledge. Then I stood behind my cartoons, ready to sell.

A few of my enterprising classmates had also cobbled together shops overnight. Justin and Nick, two sportsy boys, had pooled their resources to open a candy shop. They emptied out two large bags of goodies onto their table. The assortment had a Halloween-leftovers feel, but the unpredictable variety and arrangement, and the mere sight of so much candy at school, definitely caused a stir. Justin and Nick also had a clever pricing plan: a dollar a piece. This was pretty brilliant, because changing Monopoly money was annoying, so my classmates were encouraged to scale up their purchases: 10 candies for 10 dollars, even 20 for 20.

Jenny, who was both popular and nice, had taken an unexpected angle. Borrowing, no doubt, from Peanuts‘ Lucy, she set up an advice service. For ten dollars, you could earn a few minutes of her time. After describing your problems, she would respond with her everyday wisdom. Adding an effective, high-drama element, Jenny held these advice talks not at her shop table, but by walking her customers around the classroom’s perimeter. It was a see and be-seen phenomenon. Many wanted in.

That first week, I’m proud to say, Andy’s Art Gallery made as much buzz as Justin and Nick’s Candy Shop and Jenny’s Advice Corner. Customers found the volume and range of ready-made characters to be quite impressive. They also loved that the pictures were drawn in a black outline, which left the coloring up to them. And the prospect of ordering personalized pieces, though a bit pricier, was alluring. I spent my snack times trading cartooned index cards for crisp Monopoly bills and scribbling down the details for customers’ special requests.

By the end of the first week, I nearly sold out of my original pieces, and I had a growing list of commissions. Having promised next-day turnarounds for original works, I spent my daycare and after-dinner hours churning out new drawings. I was busy, happy, and proud. Andy’s Art Gallery was a success! And I was making a (Monopoly) living as an artist.

***

Sadly, the buzz around my gallery did not last. By week two, the warning signs had already appeared. While Justin and Nick continued to drive candy sales, and Jenny continued to lap around the classroom in hushed tones, I was getting fewer and fewer customers. People stopped by on occasion, curious to see the spread of characters. But they moved on quickly, without making a purchase. I reminded them about the commission service – I can draw anything! – but they just smiled and said things like: “I’m still working on the last one.”

Mid-week, I slashed prices in half, to no effect.

I recast my characters. In composition margins, I brainstormed new figures that I might feature. Perhaps a throwback to Ariel and Flounder. Or a few Power Rangers, paired with their Zords.

The new images earned some approving nods, but few sales.

By week three, the situation turned dire. Foot traffic died down almost entirely. I now spent snack time alone, standing behind my gallery table, racking my brain as to why my once thriving business had become a total flop. At some point, I even considered paying for Jenny’s advice. But I was too proud.

One morning, when Andy’s Art Gallery was predictably empty, Mr. B walked over and stood in front of the table, where my customers once did. He glanced up and down at the pieces, nodding.

“These are very good,” he said. “You’re a talented artist.”

“Thank you,” I said.

He lingered, then continued:

“You were selling a lot in the beginning.”

“Yes.”

“Now, not so much.”

“Right,” I sighed.

“Why do you think that is?”

Was he trying to make me feel bad?

“I really don’t know,” I said. “The drawings are just as good. I cut my prices. I don’t know.”

“Mmmmmm,” Mr. B hummed, in teacherly fashion. Then, he posed more questions: “What makes your product different from some of the others? From the ones that are selling?”

I had not thought about my problem in this way. When I did, the comparisons made me angry. Justin and Nick, who I already resented for their unrelated athleticism, were thriving under the most basic business model possible, throwing heaps of cheap candy onto a table and up-selling it. As for Jenny’s advice – how good could it possibly be? She was only nine, after all!

But I knew enough to recognize ugly thoughts and to keep them to myself.

“I don’t know,” I said.

“Well, I think you’ve got a great product here. Great art.”

“Thank you.”

“But I think about how much art I buy. Not much.”

I looked up at him, my interest piqued.

“In fact, I haven’t purchased art in years. Not because I don’t like art. I love it, actually. But… I only have so many walls in my house. I don’t have space for any more art.”

Interesting.

“So, even if I’m walking by a piece of art for sale, and I really like it, I’m not as likely to buy it. I buy a coffee every single morning. But I would never buy art every single morning.” He looked over at Nick and Justin, then back to me. “Coffee and art… they’re very different products.”

Hmm.

“That makes sense,” I said.

“So, I don’t think this situation is really a reflection on your art. I think the question is: how many Andy Malone originals does one person really need?”

The question stung. It was hurtful, but it was kind too. It was hurtful, because it made me realize that Andy’s Art Gallery would never recover. But it was kind, because I understood, in a deep and real sense, why my gallery had failed – and what that did and did not say about my artistry or my acumen. My cartoons were fine. They were just not meant for a snack-time, Monopoly-money economy.

Shortly after our conversation, Mr. B announced the end of snack. I gathered all my drawings and put them in my backpack. During lessons that day, I doodled whatever I wanted to in my composition notebook. At Daycare, I built Legos with my friends. After dinner, I chose to play with my Star Trek action figures, rather than watch TV.

At 10:20 the next morning, I did not return to my spot at the shop tables. Andy’s Art Gallery had closed for good. Hye-jin asked if I was sad. I was, and I wasn’t, so I said: “Sort of.”

We walked over to Justin and Nick’s candy shop, where I bought five tootsie rolls for five dollars. While eating my candy, I passed by Jenny’s Advice Corner. I considered whether I should buy a session. But I had no pressing questions. I had learned enough from snack time recently.