In third grade, we all got a copy of The Scholastic Book Catalog. This was a very big deal. Let me try to explain why.

First, catalogs. You may not have heard of them. Before the internet got huge, catalogs were a major way that people shopped. They were big, magazine-like books where companies listed pictures and descriptions of their products. It was kind of like if you did an Amazon search, then printed out all the results and stapled them together (except, that would be an impossibly huge catalog). After looking through all the catalog’s pictures, you’d decide what you wanted to buy. Then, you’d fill out an order form and mail it to the company. They’d ship you the products, usually in six to eight weeks, and usually much closer to eight. I know this sounds barbaric, but back in the 90s, that’s how the world worked.

For many of us 90s kids, there were two catalogs that really mattered. The first, the big kahuna of all catalogs, was the Toys R’ Us Big Book, which came with the newspaper on the day after Thanksgiving. At the time, Toys R’ Us was the toy store. It was a giant chain that peddled pretty much every toy imaginable. Their Big Book listed all the hottest holiday toys. When the catalog arrived, I spent the morning pouring through it. I took meticulous notes as I read about action figures and board games and playsets. This was how I began to draft my letter to Santa.

Nothing could top the Big Book, but The Scholastic Book Catalog came in a close second. Scholastic Books is a big publisher of children’s literature. Their catalog came not in the newspaper, but at school. It was a thick booklet, with page after page after page of desirable goodies: not only books, but box sets, stuffed animals, journals, art supplies, and so on. Large fonts in loud colors announced special deals and limited editions. It was thrilling for all of us, but especially for a nerdy kid like me.

One glorious afternoon, Mrs. J cancelled our afternoon science lesson and passed out the thick Scholastic Book Catalog. The time had come!

“Make lists,” Mrs. J said, “of the books you want. Return your completed order forms tomorrow. And make sure your parents attach their checks.”

We were, of course, more than happy to comply. We flipped through the vibrant pages, thrusting our pointer fingers against different frames:

“Look! The new Goosebumps!”

“I read that one already. What about this Ramona Quimby 2-for-1 deal?”

“Or the Boxcar Children set? It comes in a BOX.”

We laughed. Not a bad joke, to eight-year-olds.

We took out chubby highlighters and circled and starred the items we desired. We wrote lists, not to Santa, but to our parents. This was a big part of the fun: at school, we could look through the whole book and make our lists as long as we wanted, without an iota of parental constraint or commentary. That would come later, in our own homes. For now, we could dream big.

***

At the kitchen table that night, I explained the exciting new Scholastic Book program to my mother and handed her the thick catalog, with my wish list clipped to the cover. Her eyes widened at its length. She said: “Pick two.”

“Two?” I asked, hardly masking my disappointment.

“Yes, two.” She paused. “You have a lot of books.”

She was right about that. I did have a lot of books. Plus, with Mom, I never pushed too hard where money was involved. Though my mother tried her best not to talk about money around me, I understood, somehow, that money was always a worry. I picked up phrases from her phone conversations – like “month to month” or “getting by” – and intuited their general, if not precise, meanings. It was not lost on me that our apartment was small, or that my mother slept in our living room. A year or two before, my once-friend Daniel had visited the apartment and asked, innocently: “Where’s the rest of your house?” I understood better when I saw his house, which was a tremendous white thing, possibly a mansion. It had countless rooms and a huge backyard with a pool. Most impressive, it had a separate playroom for all Daniel’s toys. This included a stand-alone Lego table, which I thought was the absolute height of luxury.

But moments like this didn’t happen all that much, and mostly, I didn’t think about money. I knew not to want too hard for things. A private Lego table would have been nice, but I knew better than to ask for one. I sensed opulence as much as I sensed “getting by.” Plus, I had what I needed: books, toys, my own room – all thanks to Mom. So, if she said two Scholastic books, there was a reason. I wasn’t going to make a stink.

That night, I made a game of shortening my Scholastic wish list. Over multiple rounds, I crossed out weaker contenders and rewrote the surviving names, whittling down the list until only an elite two items remained. I don’t remember what my selections were, but I remember happily inking the titles, authors, and serial numbers onto rows 1 and 2 of the official Scholastic order form, which was a heavy sheet of paper with a light blue border.

After scribbling out my choices, I held the thick form in my hand. I noticed how empty it looked. There were rows and rows for more ordering. Front and back. A twinge of disappointment came, but it passed. There was really nothing to be sad about. Designing and executing my selection process had made for an exciting evening. Now, there was the thrill of new stuff on the way, promised for delivery straight to my classroom in six to eight weeks.

Before bedtime, I walked back into the kitchen with my order form. “I picked two,” I said, handing the list and the thick Scholastic Book Catalog to my mother.

“Okay,” she said, with a faint smile.

The next morning, sometime after my mother had left for work – she always took the early train – my babysitter woke me up, and I stumbled into the kitchen. I found The Scholastic Book Catalog waiting on my placemat. Clipped to its cover was a white envelope, labeled Scholastic Book $$$, in my mother’s distinct blend of cursive and print. I knew there was a check inside. I immediately tucked the catalog and envelope into my backpack.

***

At school that morning, after we filed in from breakfast, Mrs. J reminded us to take out our Scholastic order forms along with our homework. We reached for the thick booklets in our backpacks and clutched them as we made our way to our desks. We started to discuss our final selections with one another, until Mrs. J reminded us that unpack was a silent activity. Once seated, we placed the catalogs on our desks. Every catalog had its own white envelope, clipped or stapled to its cover. Mrs. J walked around the room, collecting the envelopes, one by one.

Collection day was fine. On collection day, there was one catalog, one order form, one envelope for each of us. On collection day, we shared equally in the joy of The Scholastic Book Catalog.

***

Six to eight weeks later, one seemingly routine afternoon, a teaching aide opened the wooden door to our classroom, interrupting Mrs. J’s lesson. Red and yellow plastic tote bags hung from her shoulders and elbows. She was exasperated. “Sorry to interrupt,” she said. “But the Scholastic deliveries are here.”

We sat up in our chairs. Some of us clapped, others clenched our fists. We whispered Yay! and Finally! and I almost forgot! The aide dropped the bags in the doorway and huffed: “This is just the first batch.”

Mrs. J seemed annoyed, but she accepted that her lesson stood no chance of continuing. She walked over to the bags and poked around, trying to get a sense of how this was supposed to work. We sat with a patient yet buzzing energy. Finally, Mrs. J began to extract bundles of books, wrapped in tight plastic, from the bags. She searched for the white labels that told our names.

“When I call your name, come up and get your books,” she said.

“Can we open the shrink wrap?” asked an observant classmate.

Mrs. J pondered this. “Yes,” she said. “But please, keep all the garbage in the middle of your desks. And don’t let any of it drop to the floor.”

Hooray! we cried, and distribution began.

The next few minutes were hectic. It was kind of like Christmas morning – if Christmas happened in your classroom, and if you had twenty-four siblings, all your own age. Mrs. J called out our names, and my classmates beelined for the front of the room, then walk-ran their shrink-wrapped piles back to their desks. Unwrapping began, followed by Can I see that’s! and Look at this ones! and You got it toos?!

Somewhere toward the end, Mrs. J called my name, and I found my way through the chaos to the door. She handed me a single shrink-wrapped package with my two new books inside. I beamed and hurried back to my seat. I broke the wrapping with my pointer finger, pulled out the books, and brought them right to my nose. I loved the smell of fresh books.

I shut out the busy-ness around me and began to examine my new acquisitions: their front and back covers, their tables of contents. I flipped through their fresh pages with my thumb, peeking for illustrations. Like Christmas indeed.

After some time, Mrs. J clapped us back to attention. The room fell silent. “Well, this is all very exciting,” she said, clearly exhausted. “Are you all happy with your new books?”

We nodded.

“Wonderful,” she said. She looked up at the clock. “Actually, it’s almost time to pack up. Can you please collect your books and other things and arrange them in a single pile?”

We made our stacks. Mine was simple: smaller book on top of bigger book, centered on my desk.

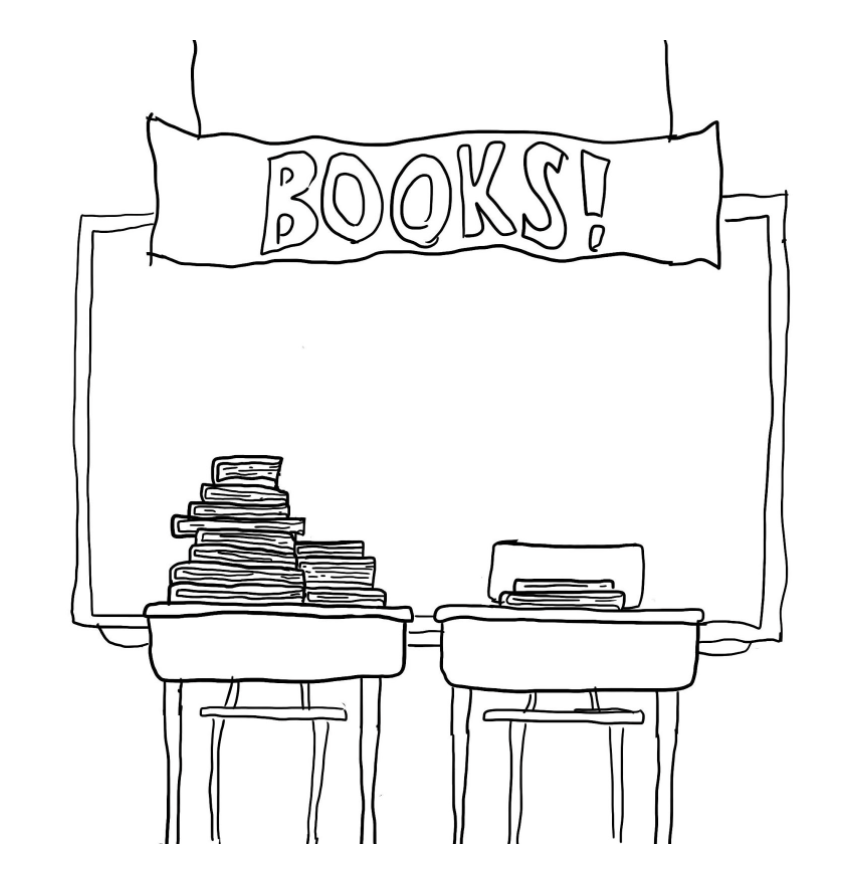

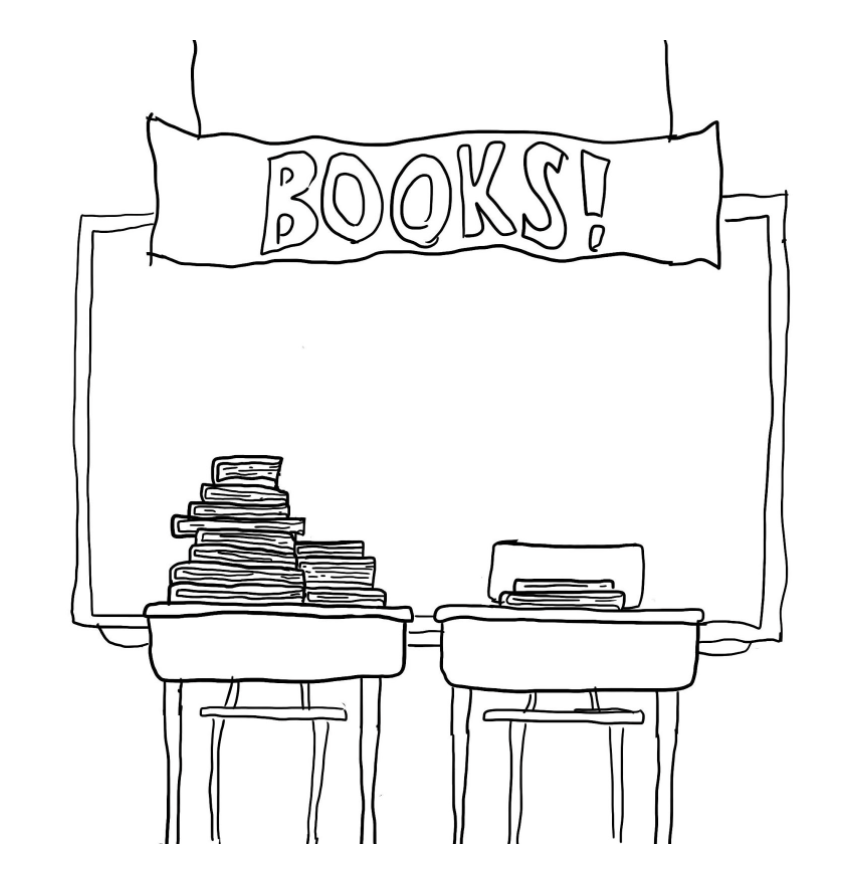

Finished, I looked around the room. The scene hit me like a bucket of ice water. Tall stacks of books. Everywhere. Stacks way taller than mine.

Oh my God, I thought.

I’m poor.

I had known that I wasn’t rich, like Daniel with his Lego table. And I had sensed enough to be careful with Mom and money. But those insights were partial and fleeting. It was now, facing stacks and stacks of Scholastic books, that I came to the conclusion, for the first time, that I was poor.

Maybe it was the volume of evidence – that everyone in the class, so it seemed, had ordered more books than me. Or maybe it was the stark visual: my piteous stack (could you even call it a stack?), flanked on all sides by Scholastic skyscrapers. Or maybe it was the public nature of the whole affair. Six to eight weeks ago, everyone had turned in a single white envelope. But the sameness had been misleading. Now, the contents of those envelopes were laid out to bear, and every one of my classmates, if they cared to notice, knew that my mother had said “pick two,” just as I knew that their mothers had said: “whatever you want.”

I felt embarrassed and angry, not at my mother, but for her; and for us, as a team. I felt the urge to defend her, to explain that these two books spoke nothing to the quality of her parenting, nor the quality of our life.

But no one said anything about my two books. I wished they would say something. I wished they would call me poor, so that I could say “I’m not!” or “So what!” or … something. Anything. But they were either too engrossed in their own piles, or they were too polite, or they were unsurprised. Whatever the reasons for their silences, I bore this moment alone.

***

When it comes to class, we bear our silences and our secrets. I’m not talking about classes in schools. I’m talking about classes in society – how some of us are richer, or poorer, or way richer, or way poorer, than one another. As you get older, you might start to talk more about class during class. You might talk about things like income and inequality and caste and capitalism and haves and have-nots. These will be important conversations. Definitely pay attention. But conversations about class between people – between friends and family – tend to happen a lot less. They are awkward and uncomfortable. Nobody likes to be richer or poorer than the person next to them. So we find ways to not talk about class, or to talk about it in big, abstract ways, even though it’s always lurking around in small ways, everywhere between everyone in our everyday lives.

That’s how it was with the Scholastic Book Catalog. I’ve wondered why my mother let me buy two books from that catalog in the first place. I really did have more than enough books at home. And I had a library card. But I see, now, what my mother’s intentions were. She knew that the other kids in my class would turn in those white envelopes. Mom wanted that for me. She knew that the envelopes would obscure our differences: that the order forms, whether two or twenty lines long, would be sealed away. She also knew how I might feel, were I the only kid in class to not turn in an envelope at all. My mother did not want me to look, or to feel, poor.

She might have succeeded – at least, for a bit longer – had it not been for the harried events of delivery day. I have been a teacher, so I am not quick to judge their mistakes. But, even now, I look back at Mrs. J’s handling of the Scholastic distribution with anger on my mother’s behalf. My mother – who took the early train to work, who picked me up late from daycare – she worked hard to obscure class from my classmates and from me. But on Scholastic delivery day, Mrs. J’s insufficient planning, and/or sensitivity, and/or awareness, undid much of my mother’s hard work. In Mrs. J’s third grade class, staring out at Scholastic book stacks, I finally figured out, despite my mother’s best efforts, that I was poor.

***

Except, I wasn’t. I figured that out many years later. For as long as I grew up where I grew up – a pretty rich town on Long Island, New York – the label “poor” made sense for me. My friends were richer than me. They had bigger houses, like Daniel. They built big stacks of things; books were just the beginning. Gadgets, vacations, tutors, summer programs. Compared to the people around me, sure, I was poor.

But then I left Long Island and went off to college. I definitely met a lot of rich kids at Harvard. But I also met a lot of not-rich kids, and a lot of less-rich kids. Clustered together in classes and dining halls, the student body displayed a range of wealth and geography and experiences, all of which got me thinking. Meanwhile, in my classes, I learned more about class than I ever had in high school. After graduating, I took a teaching job in the rural Mississippi Delta, one of our country’s objectively poorest regions, in terms of how much money people make (though I would find the Delta to be an incredibly rich place, when it came to non-monied things, like culture, history, community, and love).

My early twenties shook the certain conclusion I had come to as a third grader, staring out at those Scholastic book stacks. Yes, I had been poor-er than the other kids in my class. No doubt about that. But had I been poor? No. Not really. I had my books, and my toys, and my own room. I never wanted for a meal. The more I grew up, the more I began to entertain the possibility that, on a national scale, mom and I might have been working class, or even middle class. In fact, on a global scale, it was possible – even likely – that we had been rich.

This was an uncomfortable thing to acknowledge. It felt like a betrayal of my mother, for whom month-to-month and getting by and sleeping in a living room and raising a single son among Daniels and their mothers were all very hard, very real things. To say that I grew up rich would be, somehow, to deny her struggle and her sacrifice.

Even to this day, I don’t talk to my mother about my realizations. I don’t talk to her about the fact that we were poor, but also rich. She and I, like so many others, are poorly practiced when it comes to talking class.

I trace that silence back to third grade, when I chose not to tell my mother about the Scholastic book stacks. I kept that thought – I’m poor – to myself. I managed the feelings: the sadness and confusion I felt for myself, and the anger I felt at Mrs. J, for allowing those stacks to happen. For creating a little public record of what our families could and could not afford.

But now, I think the stacks were not the problem. The problem, I think, was the silence that surrounded them. It was a silence that we all worked to preserve – except maybe, to his credit, my obnoxious once-friend Daniel. He said something, at least. But the rest of us? We never said anything. We never talked about the fact that our stacks were different heights, nor that all of us – even the poorest among us – had taller stacks than many, many children in the world. Instead of conversations, there were moments, here and there, which made class more or less visible. Moments which, over time, led me to figure things out: that I was poor, and that I was rich, and that this was all too much to talk about.