At some point during second grade, somewhere between RJ and Alan, my best friend was Steven. (I had a lot of best friends that year. Just one of those years, you know?). Steven had been in my First Grade class, too. But he had arrived at my birthday party that year with the worst, most boring present imaginable: a giant, floppy book with a shiny white cover, called…

My First Dictionary.

My First Dictionary! For my birthday! Can you believe it?

I pretty much wrote Steven off after that, but we found one another again in second grade. We began to hang out during recess because neither of us was good at sports. I’m not sure what Steven’s issue was, but mine was clear: I had gotten fat. Quite fat. So I steered clear of the soccer field, where all equally awful versions of tag took place. Instead, Steven and I developed clever, fun, non-athletic playground games. We pretended to be spies, we built forts out of twigs, we debated the most valuable superpowers. Pretty soon, we were best friends.

By the way, I did address the birthday present with Steven. He explained that My First Dictionary had been his mother’s idea. In reflection, this made total sense: what child in their right mind gifts My First Dictionary? I forgave him.

One day at recess, I asked Steven for a playdate. His response surprised me. He shifted his eyes and rocked back and forth and uttered a few “ums” before landing on “I’m not sure.” Given his discomfort, I guessed that Steven did not have many playdates. It was possible that Steven had never had a playdate.

It felt rude to ask him that, so I suggested that we loop in our mothers: “You ask your mom, and I’ll ask mine. They’ll call each other and figure it out. That’s how playdates work anyway.”

Steven nodded and we returned to our debate: invisibility vs. telekinesis.

***

Later that night, my mom picked up our corded phone in the kitchen (conduct an image search for corded phones. They were real!).

“Hello?” said Mom. “Oh yes, just a second.” She covered the receiver with her palm. “Andy,” she whispered, unhappy to be caught off guard. “Who is Steven?”

“That’s my best friend.”

“I thought RJ was your best friend?”

“No, it’s Steven now. I asked for a playdate. He’s great!”

That was sufficient. The moms did what moms do, and later that week, I got to bring a note to school, explaining that I would not take Bus I to daycare. Instead, Steven’s mother would pick me up for an after-school playdate. This was all very exciting: a best-friend playdate and a change in my routine.

***

Steven lived close to our school. Within five minutes of meeting his mother at dismissal, we were standing outside the door to their apartment, which was the second story of a multi-family home.

Steven’s mother took out her key, then turned to me. “We have a no-shoe rule,” she said, warm but firm. She and Steven took off their sneakers and arranged them on a nearby mat. No-shoe policies were unfamiliar to me, but I appreciated the clear direction. I untied my laces as Steven’s mother opened the door.

The apartment was scary clean. Its white walls and light furniture were blinding, reminiscent of the haunting Oompa-Loopma factory from Willy Wonka. Steven waited inside the door frame, comfortable in the cleanliness of his own home. He did not sense that I was nervous.

Once inside, Steven’s mother ushered us past the white couches toward the kitchen table. Snack time, I assumed. My nerves softened and I grew excited. I loved to try out my friends’ snacks (the best, right?).

But the kitchen table was not set for snack. Instead, there were two side-by-side workstations. A single sheet of white paper sat atop each, alongside a small cup of water and an open watercolor set. The watercolors were the Crayola kind, with yellow-orange plastic and eight paint ovals in a row.

This was unexpected.

“Take a seat,” Steven’s mother said. I waited for Steven to claim his chair, then hoisted myself onto the other one.

“Thursday is our art lesson,” Steven’s mother explained. I nodded to be polite, but I was beyond confused. Art lesson? After school? With what teacher? And why?

Thursday is our art lesson. What happened Monday through Wednesday?

I looked to Steven, but he was calm and comfortable, as he had been at the door. Of course, he was used to this.

“I like art,” I said, not knowing what else to say.

“That’s good,” Steven’s mother said.

“And watercolors are my favorite,” I said, which was true. I spent plenty of time at daycare painting watercolors. My mother said that my bold color choices reminded her of Matisse (also worth an image search. Check out his goldfish!).

“Aaah, that’s also good,” replied Steven’s mother, grinning slightly at the corners of her mouth. “But today’s lesson is not about watercolors.”

Oh.

“Today’s lesson involves…”

She paused, turned around to the kitchen counter and reached for something, then turned back to face us.

“…toothpicks!”

Toothpicks?

Steven’s mother held up a pink and blue toothpick box. She placed one toothpick in front of Steven, then one in front of me. She folded the small box and returned it to the counter.

“Yes,” she said, “today’s lesson is about toothpick art. You are to create a piece of art using your toothpick and the paint.” She looked to her son, then to me. “Any questions?”

I had tons of questions. Why?, first and foremost. But asking questions seemed maybe rude, or maybe stupid, so I shook my head no. Steven sat still.

“Great,” his mother said. “You can begin.”

Steven’s mother disappeared into the kitchen, leaving Steven and me to our toothpicks and blank papers. We sat for a while, puzzled by the task before us.

“What are you gonna draw?” I asked Steven, hoping to bring some talk, if not play, to this very odd playdate.

“I don’t know,” he said. “You?”

I thought for a bit. I usually tried to make creative choices with my art, but this toothpick constraint was already challenging. Plus, I was still processing everything happening around me. “I think I’ll just draw an outside scene.”

“Yeah, me too,” he said.

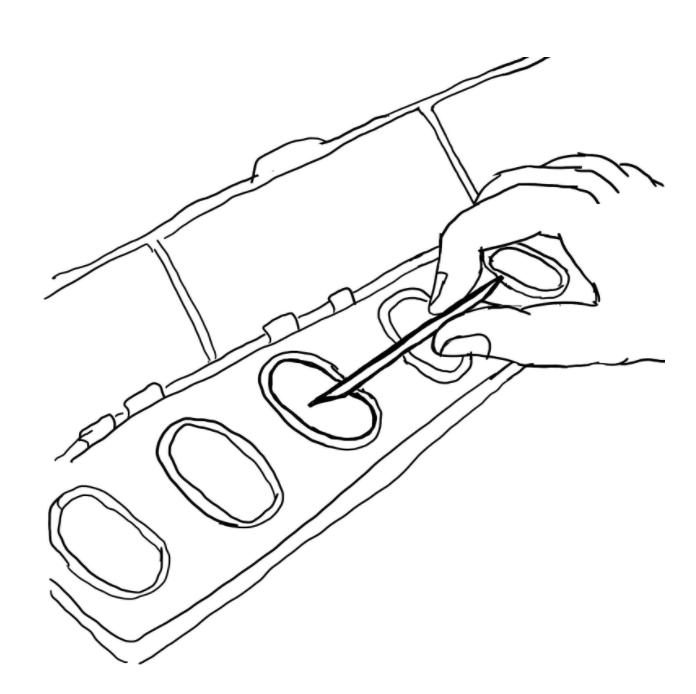

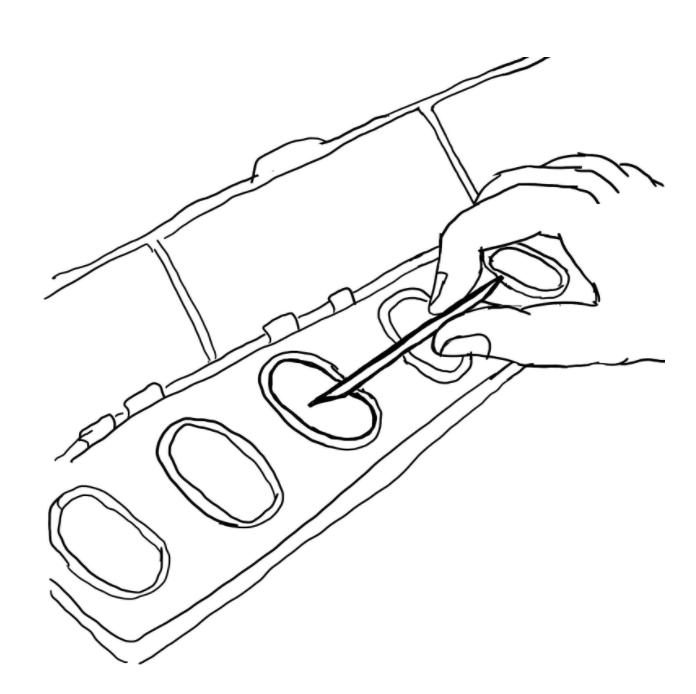

Well, we at least had a plan. I reached for the toothpick. I decided the best way forward was to treat it like a brush. I dipped the toothpick in the small cup of water, then scraped it against the watercolor kit’s green oval. After a few seconds, the paint became paint-y. I lifted the toothpick toward the paper and traced a line of green grass toward the bottom of the page. It was skinny and faint. Unsurprisingly, the tiny piece of wood could not hold much paint. Still, I was making progress. I brought the toothpick back to the water, back to the green oval, and back to my paper, darkening the grass line. This was going to take a while, but it would work.

Steven watched me, decided he liked my approach, and began to do the same. Having discerned our toothpick-painting method, we began to talk about other things: school, our classmates, cartoons. Batman: The Animated Series was at its peak (I cannot recommend this series enough. Again, you’ll need to make peace with pre-Pixar 2D animation. But the characters and stories are just fantastic. Some of the all-time great villains; Mr. Freeze and Poison Ivy top my list). Steven and I laughed and enjoyed ourselves as we traced our toothpicks against the paper, wiped them clean against paper napkins, and scratched them in new colors: brown for tree trunks, red for flowers, yellow for round suns in upper right corners.

After some time, Steven’s mother returned from the kitchen. “All right,” she said. “Let’s see what you did.”

I looked down at my landscape. Not bad, I thought, especially given the circumstances. I had milked this little toothpick for all it was worth. My painting was nowhere near my best – certainly not a Matisse – but it was a solid depiction of the outdoors. Steven seemed satisfied with his landscape, too.

“Very nice,” Steven’s mother said, looking at our work. “You were both able to create a full composition, using the toothpick.”

Great, I thought. We had passed the lesson. Maybe now we could go play!

“However,” she said, as she walked back around the table to face us. “I do have one critique. Something for you to think about.”

Oh no, I thought. Had we done something wrong? I looked over at Steven, but he seemed calm, more accustomed to his mother’s criticism.

“You used the toothpick as a brush.”

She turned around and took a clean toothpick from the pink and blue box on the counter. She turned back and continued.

“So, while you used the toothpick to create your art…”

She paused.

“…your art does not reflect the essence of the toothpick.”

Huh?

Steven’s mother took her clean toothpick and leaned over the table, immersing it in my cup of water. She then brought it to the paint set. Rather than scratch the tip against the green oval, she rolled as much of the toothpick as she could against the palette, smooth rolls, back and forth, until the whole sliver of wood was covered in paint. Her fingertips turned green, but she didn’t seem to mind. Then, she brought the toothpick to my piece of paper, and, without asking, pressed the small wooden stick against it. She did this a few more times, turning the toothpick this way and that, deliberate yet carefree. Finally, backed away.

She left behind a cluster of toothpick-length green lines, angling in all directions. There was not a smooth or continuous curve in sight. It was for sure ugly. But it was for sure the top of a tree. And it was for sure curious and captivating. Though chaotic and messy and unfamiliar, these contours felt far more themselves. The lines I had drawn, just inches away, now seemed strained and unnatural; gestures at something they were not and could never be.

“The essence of the toothpick,” Steven’s mother said. “Do you see?”

I did. I had no idea what the word essence meant. Maybe I could look it up in My First Dictionary. But I saw what Steven’s mother meant for me to see: the difference between my wanna-be contours and her jarring, yet honest, toothpick prints.

I understood her lesson.

For a moment, I felt sad, as though I had gotten the wrong answer. Maybe I was not a very good artist, after all. Matisse surely would have appreciated the essence of the toothpick.

But that feeling passed quickly, due largely to Steven’s mother’s demeanor in the minutes that followed. She did not seem upset or disappointed by our performance. In fact, she did not say anything more about it. She helped us clean the table, set out some snacks, and asked about our day.

It felt odd, but reassuring, to be ushered back into a normal routine, just moments after being exposed to some profound truth. It was as if Steven’s mother had known, from the start, that the essence of the toothpick would be beyond us. It was as if she had expected us to paint half-hearted imitation landscapes all along. We were supposed to stumble, such that we could appreciate the scratchy toothpick marks once she revealed them. We were to fail, such that we could learn. And then move on.

***

Move on we did. After snack, my playdate with Steven continued in familiar veins. Steven showed me his toys, we played, we talked. My mother came to pick me up after work. On the car ride home, she asked how it went.

“It was fun,” I said. “You can’t wear shoes in their house.”

“Oh?”

“Yeah. It’s very clean. And we had an art lesson.”

“An art lesson? With who?”

“His mother,” I said. “We painted with toothpicks.”

“Interesting,” Mom said. “I’ve never heard of painting with toothpicks. How was that?”

I thought about explaining the lesson, about how when you paint with toothpicks, you must capture their essence. But it would be too hard to explain, I decided, even though Steven’s mother had made it so clear, just a few hours before, with so few words.

“It was… different,” I replied. I almost left it at that. But something felt off. Like I owed the afternoon a little bit more.

“It was a really good lesson,” I added. “His mom is a good teacher.”

“That’s good,” my mom said. She drove on and asked about dinner. I tucked the playdate and the art lesson and the essence of the toothpick away, finding space for them somewhere among the things in life I wanted to remember.