This kindergarten lesson began like any other. My teacher, Mrs. M, called the class to the cornflower blue carpet. We gathered around its perimeter, sat criss-cross applesauce, and looked up at Mrs. M. She smiled from her big wooden chair.

“Today,” she said, “we are going to discuss how the dinosaurs went extinct!”

Well, this was exciting! I loved dinosaurs. My favorite movie was The Land Before Time (I highly recommend this film, though, fair warning: it’s terribly sad. Plus, you’ll need to forgive the basic, 2D animation of the early 90s. There was no Pixar yet!). I also owned a ton of books about dinosaurs. Early on Saturday mornings, before Mom woke up and before cartoons came on TV, I would sit on my bedroom floor and leaf through pages and pages of T-Rex, Triceratops, and Stegosauri. My favorite toy was a set of seven pocket-sized, neon-colored plastic dinosaurs, which cost 99 cents at the grocery store, and yet were more awesome than most expensive toys. I took them everywhere: to the park, to the beach, and yes, even to school. There’s a good chance that a few of those dinos were in my pocket, keeping me company as I sat on Mrs. M’s carpet. If so, I’m sure they had mixed feelings, learning about their own extinction.

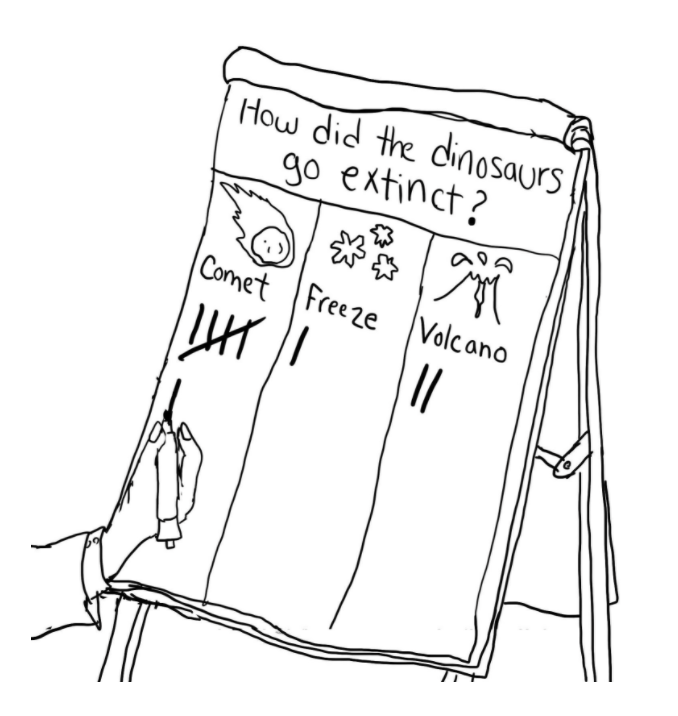

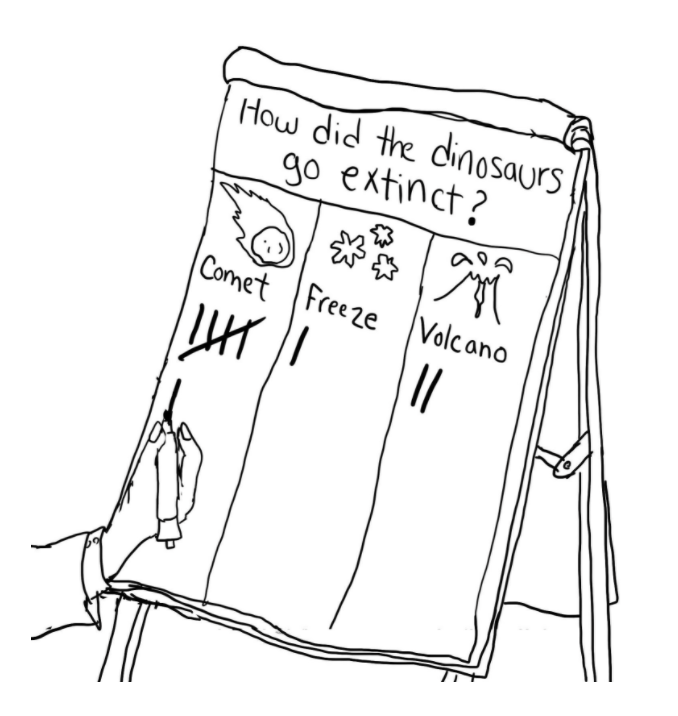

Mrs. M flipped over a sheet on the easel to reveal a fresh anchor chart. She had already written the question of the day, in big loopy letters, at the top of the paper: How did the dinosaurs go extinct? Beneath the question were three crisp and evenly-spaced columns. Heading each column was one word with one illustration:

Comet | a rock with a purple tail.

Freeze | light blue snowflakes.

Volcano | a brown mountain spewing red-orange lava droplets.

Next, Mrs. M summarized each of the extinction theories. A very good student and lover of dinosaurs, I listened intently, staring at each cartoony column header as she went. Soon enough, it came time to vote.

I voted early. Maybe I volunteered, or maybe Mrs. M was working off of an alphabetical class list. Either way, that I voted early is important to this story.

“Andy, how do you think the dinosaurs went extinct? Comet, freeze, or volcano?”

“Volcano,” I chimed. To me, volcano was the obvious choice. I knew snow to be inconvenient, but harmless. If humans could survive winters, surely dinosaurs could do the same. And what were the odds, really, of a comet smacking into our planet? A volcanic eruption seemed much more likely: volcanoes were already here on Earth, gushing lava and ash with some regularity. Plus, I really liked Mrs. M’s illustration. The lava droplets were exciting!

Mrs. M nodded, then drew a thick, vertical black tally mark under Volcano.

The next kid voted: “Comet.” Mrs. M added a tally to the first column.

The voting continued:

“Comet.” Tally.

“Comet.” Tally.

That’s weird, I thought. Three comets in a row?

Two comets later, Mrs. M paused the vote and made a big show of what to do now that we had reached five tallies. “We don’t put the fifth tally next to the fourth,” she warned. “We draw the fifth tally on a diagonal, like this.” She slowly dragged the marker from the top right to bottom left of the tally cluster, eliciting a range of enthusiastic ooooohs and aaaaaahs.

I wasn’t too interested in this diagonal tally. Group by fives, sure, very helpful. My concern was with the lopsided vote. What was going on with these comet fanatics?

The voting continued. To my annoyance: comet, comet, comet. A renegade freeze, thank God. Another comet. And another!

“Now, how should I draw this next tally for comet?” Mrs. M asked. “On the…”

“…DIAGONAL!” we cried.

“And how many comets?” she asked, tapping both tally clusters.

“TEN COMETS!”

“Ten comets! Very good. Do you see how our groups of five make it easier to count?”

Yes, I thought. Yes, I see all ten comet tallies. I see them clear as day.

The lesson wore on, just like that, strings of comet votes interrupted only now and then by a dissenting freeze or volcano. I was surprised, confused, and very upset. Had I missed something? What did my classmates know about comets that I did not? And how did they know it? I always paid attention! And I read all those dinosaur books! How could I be behind?

Maybe, I thought, my classmates were all just copying each other. If so, that was unfair. They should have to explain themselves.

The voting continued.

Comet.

Comet.

Comet.

Were we going to talk about this?

But the lesson went on, absent discussion, until the last vote was cast. I stared at the final count. Two freezes, four volcanoes, and lots of comets. Enough comets to count by fives.

As I watched Mrs. M translate the tallies into big, regular numbers, I felt lonely and dumb. I understood how to tally. But clearly, I did not understand extinction theories.

Finally, Mrs. M announced comet as the official winner. I rocked back and forth a bit, hoping that the time had come for a conversation. Why was it comet? What was wrong with volcano? I was not stubborn. I could be convinced. But I needed reasons. My curiosity was tense and desperate.

But the lesson was over. Mrs. M dismissed us back to our seats. Snack time.

***

I can see, now, that the purpose of Mrs. M’s lesson was not to debate extinction theories. This was a math lesson. She was teaching us how to tally, using dinosaurs as an engagement tactic.

Mrs. M deserves a lot of credit for that. There are plenty of boring ways to teach kids how to tally, like asking them to count tiles, or sticks, or little plastic bears. Tallying theories of dinosaur extinction is definitely more interesting than any of those. Plus, the lesson worked. I definitely learned how to group tallies. Mrs. M’s modeling was memorable and clear. I remember, to this day, her thick black marks and her dramatic pauses on each multiple of five. I’m sure that most of us drew the fifth tally on the diagonal forever more.

But sometimes during lessons, we learn things that teachers don’t mean for us to learn. During a literature seminar, we might read a scene of dialogue out loud, and thereby discover that we have a special knack for acting. During a science lab, we might work in groups, and thereby learn that we are an excellent (or not so excellent) team leader. During a history lecture, we might develop our own secret way to take notes super fast.

Sometimes during lessons, we might learn things that have practically nothing to do with “learning” at all. For instance: we might learn that we have a major crush on the person sitting across from us. Or we might learn we get hungriest in the late morning. Or we might learn that all we want to do in this world is to write stories, or to draw cartoons, or to design buildings, or to climb Mount Everest. A very famous educational philosopher, John Dewey, coined a helpful phrase for this idea. He called it collateral learning. Collateral learning is all the learning that happens, sort of by accident, alongside the teacher’s intended instruction. Dewey says that a lot of this accidental learning becomes more valuable and lasting than the learning we’re meant to do on purpose.

For me, Mrs. M’s math lesson involved a lot of collateral learning, which is maybe why I remember it so well. What I remember, alongside the diagonal tally marks, is the lonely, dumb feeling I had at the edge of that cornflower carpet. How I felt lonelier and dumber with each subsequent vote. How I wanted so badly for a conversation, for an explanation, that never came.

I don’t fault Mrs. M for my feelings. How could she have known? For her, this was a home-run lesson. It was creative and captivating. She drew clear tallies and heard confident choral responses. For my classmates, this lesson was straightforward. It was an opportunity to show what they knew about tally marks. For most of them, I’m sure, the lesson was insignificant and has become a lost memory.

But for me, this lesson meant something. The carpet’s edge, the crisp columns, the comet landslide. They have lingered. I remember the day when I learned to group my tallies. It was also the same day I learned how hard it can be to disagree.