Remember, I was fat. And I was totally fine with that.

After the Doughboy, I kept finding ways to own, and even to enjoy, my fatness. I refused to feel sad or embarrassed about the “fat” things that happened to me. Instead, I took these experiences on my own terms. I transformed them into funny stories and I told them with pride.

For example, there was the time I went to the town carnival with Ashley. We were boarding a ride, and I got on first. I tipped the carriage so far to one side that the attendant’s eyes bugged out, cartoon style. To solve for the tippage, he directed both Ashley and her father to sit close together, exactly opposite me, combining their weight to balance out mine. Hilarious!

Then there was the time I got stuck in my costume during Pippin, the fall musical. My director asked me to try on a metallic turquoise shirt. I squeezed into it … but I could not squeeze back out. My friends, Brad and Jimmy, had to peel the shirt off. In its place, I wore the only other thing from the costume closet that would fit me: a peach-colored bathrobe with a white doily collar. Too funny!

Those might sound like terrible experiences, but if you heard me tell them out loud, you’d feel differently. You’d see me smile, and you’d hear me laugh, and you’d realize that I had no sadness or shame when it came to these fat trials. Soon, we’d be laughing together. Fat Andy was a real ham.

He was also pioneering. Fat Andy invented something called the waffle sandwich, which is two toasted Eggo waffles between two untoasted pieces of white bread. What a snack! (If you decide to try this out, don’t tell your parents that you got the idea from this book. Just keep that recipe between you and me, okay?). Another example: along with his friend Michelle, Fat Andy founded the Obese Club, an exclusive social organization that met at TGI Friday’s. There, we discussed the finer points of fat life over a dish called Cheesecake Indulgence. (I think this dish has since been discontinued, which is a true tragedy). Some of our thin friends became jealous and tried to form a “skinny club” in response. The skinny club was, of course, boring and short-lived.

Fat Andy really was great.

I loved being him, right up until that morning in ninth grade gym.

***

Coach D lined us up outside. It was first period. There was a slight chill in the air.

“It’s a beautiful day, my friends!” he bellowed. “The perfect day for your mile run!”

Oh, God. I hated the mile run.

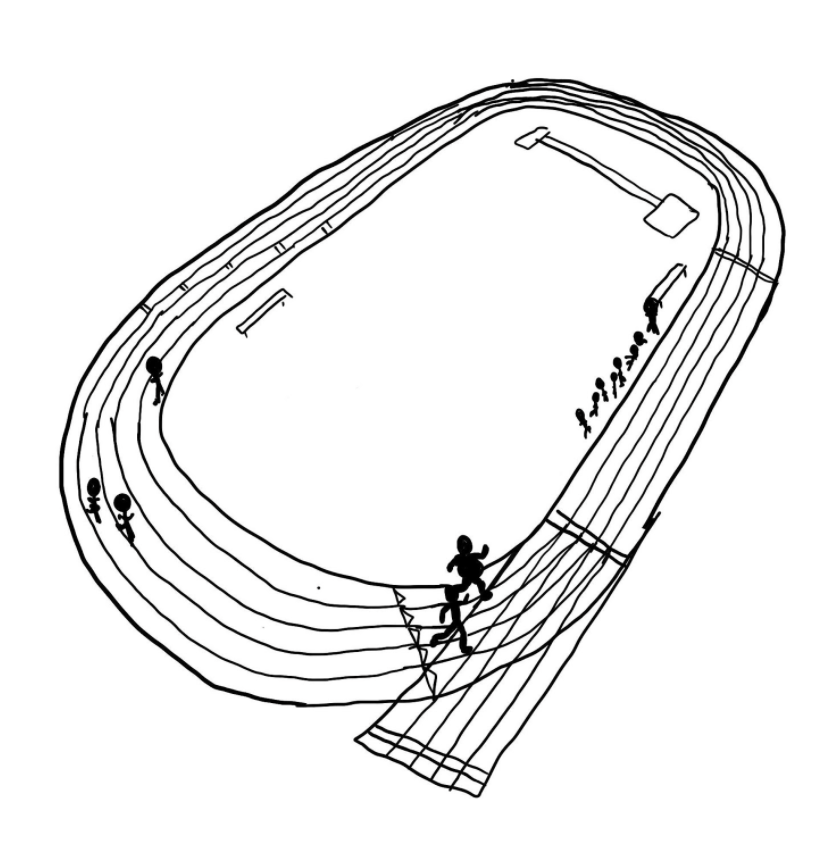

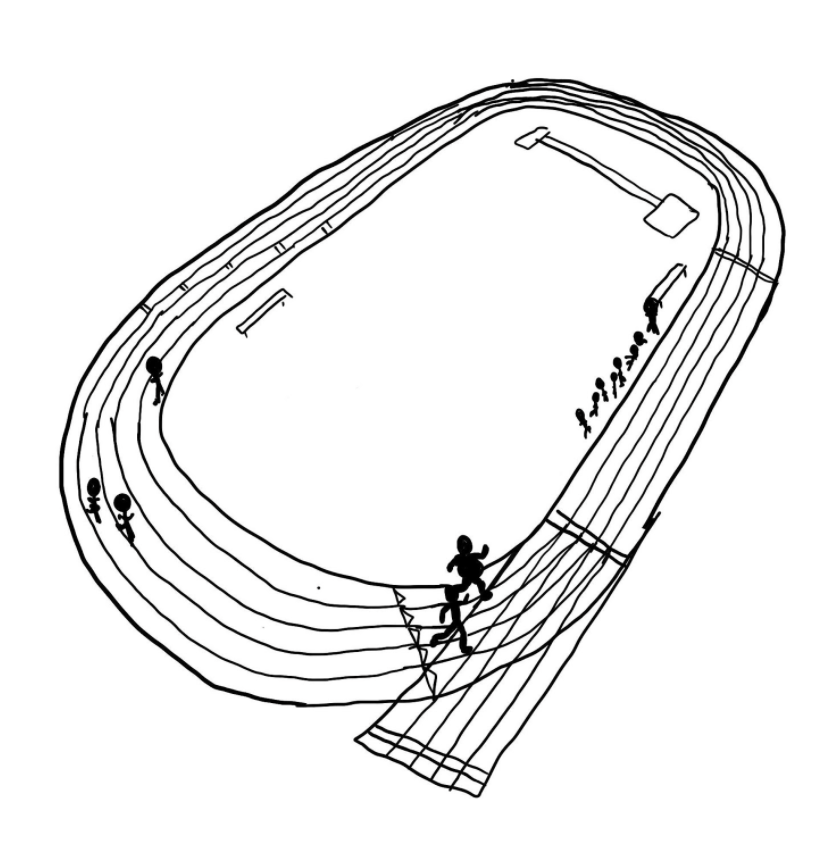

Twice a year since sixth grade, we ran the mile in gym class. Once every fall, and then again every spring. (Why? WHY?). The coaches recorded our mile times in an ominous manila folder, which followed us from year to year, like some inanimate stalker.

The mile run was awful for three reasons. First, it was a mile. Second, it was a run. Third, there was nothing else to it. There was no context against which I could play my fatness. No opportunity to tell funny stories, no chance to display my creativity or intelligence or kindness. On the track, I could only be fat and slow.

And boy, was I fat and slow. The mile might have bothered me less, had its set-up not been so humiliating. Once we finished our four laps, we were to recover and relax on the side of the track. As a result, those of us who did not finish early – like me – found themselves very much on display. Every year, by the time I finished my second lap, there was already a jocky cohort of six-minute milers lounging about. Honestly, who were these junior Olympians?. They stood or laid in the grass, stretching out their quads and laughing with one another, watching me waddle by as Coach screamed out my lap time.

By high school, the mile was familiar torture. It was unpleasant but unsurprising. I had no reason to suspect that this spring morning in ninth grade would be any different. We gathered at the pristine white starting line. I moved to the inside lane, because it was shortest; and to the back of the pack, because, duh. Coach D blew a starting whistle, enthusiastic beyond reason. I eased into a light jog.

Coach D had a minimum expectation that we run the straightaways. If we absolutely had to (I had to), and if we were really, really winded (I was really, really winded), we could power-walk the turns (oh, I absolutely did). “But,” Coach D had said, “I want to see every one of you run those straightaways.”

Some kids straight up ignored Coach D and strolled the whole time, even though they were skinny. I, however, did as I was told. I did not want Coach D to think I was lazy. I knew how fat kids got As in gym class: demonstrative effort plus utter compliance.

So, I ran the straight parts of the track, as best I could. I walked the turns, as best I could. I was still way behind the jocks, which was expected, and barely ahead of the deliberate walkers, which seemed unfair.

Huffing and puffing, I crossed the starting line for the second time. Halfway done! There was that jocky crew, finished already, eyeing me with both judgment and indifference. Same old.

By the third lap, my straightaways grew belabored. I kept trying to run, in case Coach D was watching. But I had to catch my breath, more than once. When I reached the starting line again, most of the class was done. They were stretching, relaxing, watching.

I kept going. One more lap. Then I would be free of the mile run until next fall.

The final lap started normally, just me and some lazy walkers. But halfway through, on the far side of the track, something unexpected happened. An upperclassman jock, who I did not know, who had finished his own run minutes before, ran across the field. Towards me. When he reached me, he ran around to the second lane and aligned himself with my right shoulder. He slowed down and began to jog at my pace.

This was very strange.

“Hey,” he said.

“Hey,” I huffed between hard breaths.

“I’m gonna finish the run with you. Okay?”

Very strange.

“Sure,” I managed. With little breath to spare, I was not in a position to inquire or protest.

We rounded the turn to the final straightaway. I’m gonna finish the run with you. Why? Why would he finish the run with me?

I saw the white line, off in the distance; and the rest of our gym class, lined up on the grass beside it. I began to make sense of what was happening. This Stranger-Jock didn’t want me to cross the finish line by myself. He saw how hard I was working. He thought I deserved some company; or maybe even some protection, from his own Junior Olympians. I could not believe it. Such kindness was unprecedented, especially in high-school gym. But here he was, Stranger-Jock, matching my pace. Step by step.

For the first time, I had someone beside me on the straightaway. For the first time, I would not finish the mile run alone.

We approached the finish line and the crowd.

Then it happened. Stranger-jock raised his left hand, slapped my butt cheek, oinked, and sprinted ahead. The Junior Olympians cheered.

I started a diet the next morning.

***

To this day, I’m not entirely sure why I afforded that one moment so much power in my life. After years of owning and loving my fatness, I allowed one stranger to break me. It was like that flip of the switch with Dr. L. For months, the Rules had terrified me; then one day, they meant nothing. For years, fat teasing had bored me. Then, one morning, one slap on the ass, and I decided to leave Fat Andy behind.

I was not sure how to diet. I intuited some broad, basic rules, like “no dessert.” But I struggled to develop an actual plan. I was so used to mindless eating. It felt confusing to approach food with intention.

I stumbled along that first week, avoiding sweets and making the best choices I could. Then, that Saturday night, I had a breakthrough. I was babysitting. Virginia, the woman I sat for, had left her Weight Watchers book out on the kitchen counter.

Ah ha! I thought. A book. I did not know how to diet, but I certainly knew how to study.

After I put the kids to bed, I hurried to the kitchen and opened the thick, floppy Weight Watchers text. Inside the front cover, I found a cardboard contraption called the “Points Calculator.” I played with it a bit. There were sliding tabs, labeled CALORIES and FAT and FIBER. What even is Fiber? I thought. (Honestly, I still don’t really know). When I slid the tabs, the calculator revealed different point totals in a small square at the bottom. I was into this.

I kept reading. I learned all about the Weight Watchers Points system. I thought it was brilliant. Every food item became a number:

One slice of bread = two points.

Two scoops of peanut butter = six points.

One pizza slice = nine points (meep).

To diet, all I had to do was tally my food throughout the day. According to some complex grid, based on my current weight (over 200 pounds…let’s leave it there), I was supposed to eat fewer than 24 points a day. I knocked it down to 21, because, you know, that inner Achiever loves a challenge.

The rest of the book was a diet catalog, an alphabetical directory of foods and their point values. I spent the night reading it. I looked up the foods that I liked to eat and committed their point values to memory. I was intimidated by much of what I learned. Waffle Sandwich was definitely out. And I would never think of cheese the same way again.

I spent some more time with the calculator. I slid the tabs back and forth, trying to figure out the rules that governed the points. It wasn’t so hard: A point was 60-ish calories, or 2-ish grams of fat. Fiber could knock off some points, but I ignored that. I practiced a bit. I read the labels of Virginia’s snack foods, calculated their points, and then checked my work in the Weight Watchers book. By the time Virginia got home, I had it all figured out.

***

For the next few days, I tried to journal all my points. It was fun, at first, but it soon turned stressful. Logging the points took time. And it was unbelievably easy to eat twenty-one points in a day. Every time I wanted a snack, I’d calculate the points. Then, I’d realize I couldn’t afford that many points. Then, I’d feel disappointed. Then, I’d think of something else to eat. Then, I’d calculate those points. I’d realize I couldn’t afford that snack, either! I would repeat this sad cycle, over and over again.

This was not going to work. I had to regroup.

I eventually decided that it would be easiest to set a daily routine, one that worked for my life and that would always keep me under 21 points. Here’s where I landed:

Breakfast: 1 bowl Cheerios = 5 points

- Cheerios (1 cup) = 3 points

- Skim Milk (½ cup)= 2 points

Lunch: ½ turkey sandwich = 4 points

- Turkey Slices (3) = 2 points

- 1 piece bread (1) = 2 points

Snack: 1 cup grapes = 3 points

Dinner: whatever Mom makes (9 point margin).

If dinner was lighter, and there were points left over, a certain brand of raspberry sorbet bars – two points each – made for a passable dessert.

I ate this way for three months, through the end of freshman year and for the whole summer that followed. With the regimen in place, my diet became easy. I knew what I had to do. And I did it. End of story. I did not crave sweets, I did not mind hunger. I did not once think of Stranger-Jock, who had inspired this whole diet in the first place. I detached and I ran the program. Cheerios, turkey, grapes, dinner. A raspberry sorbet bar, every now and then.

***

By the end of that summer, I had lost over sixty pounds. Fat Andy was gone.

Labor Day weekend, my friend Sammi and her mother took me shopping for new clothes. “You need clothes that fit,” Sammi’s mother said. “You are swimming in your own t-shirts.”

Sammi chuckled. “You really are, Andy.”

I guessed they were right. I had not noticed. I knew I had lost a lot of weight, because the scale said so. But I honestly didn’t feel very different.

In fact, when Sammi, her mother, and I arrived at The Gap, I was still reaching for extra larges.

“Andy, you’re being ridiculous,” said Sammi, thrusting a pile of medium t-shirts into my arms. “Go try these on.”

She was right. They fit. Unbelievable. I chose three, and I remember each of them: maroon, olive, navy.

Driving back into town, Sammi’s mother surprised me with a question. “So, Andy, now that school is starting back up, are you done with this diet?”

Sammi jumped in. “You should be! You look great. You don’t need to lose another pound.”

“You really don’t,” affirmed her mother.

“Seriously. Like, you’re getting maybe even too skinny.”

Too skinny? What a ludicrous thing to say. From Sammi, nonetheless, a lifelong skinny person.

I had not thought about when I might stop the diet. The diet was so different from The Rules. There was no list of things to cross off. I thought when I was done, I would just … know. I would look in the mirror and feel something: some kind of feeling I assumed skinny people, like Sammi, felt all the time. A confidence, a certainty. The way Fat Andy had felt, before I had wished him thin.

I hadn’t found that feeling yet. But Sammi and her mom were probably right. I’d probably find it the first day back at school. I imagined the reactions I would inspire as I walked down the halls: shocked faces, abundant praise, maybe even flirty glances. That’s where I would find the missing feeling.

“Yeah, I’ll probably stop when school starts,” I said.

“Good,” Sammi said.

“Yes, that’s great,” her mom said. “You know, we’re getting a little worried about you.”

Worried about me? Please.

“No need to worry,” I said. And I meant it. After all, I wore mediums now.

***

I chose the maroon shirt for my first day of sophomore year. I tugged at the shirt as I approached my school building, an ugly-as-sin, mid-century slab and brick fortress. I worried that the medium was maybe too tight. Too late now, anyway. I was at the front doors.

Here we go, I thought. Skinny Andy’s debut.

The debut did not go as I had imagined. I walked through the lobby and the hallways. I saw friends and strangers and teachers. There were a lot of shocked faces. But they were not good-shocked. They were too shocked. It felt like I was a joke, somehow; even bigger than before.I did get a lot of praise. But the tone of the praise was all wrong. Compliments seemed forced and measured, tinged with something like suspicion, or pity. There was not a single flirty glance.

It was terrible. By late morning, I was speed walking through the hallways with my head down. I did not want to be seen anymore. I just wanted the day to be over.

When I finally got home, I felt hungry, which I had not felt in a long time. I opened the fridge and grabbed a bunch of grapes. As I snapped them, one by one from their twiggy vines, I tried to make sense of the day.

Something was not right. I thought the diet had been working. I knew I was thinner. Maybe even thin enough. But the feeling I had in those hallways – that was not a feeling that skinny people had. No way. I did not feel confident, or comfortable, or certain in my body. In fact, I had never resented my body more.

I missed Fat Andy.

***

I had no idea how to respond to that first day, so I didn’t. I stayed the course. I kept dieting. I thought, maybe, in time, things would work out the way they were supposed to. Maybe the initial shock would wear off. Maybe the compliments would grow genuine. Maybe the glances would turn flirty. Maybe, if I lost just a few more pounds, I would become the good-looking, skinny teenager that I had decided I wanted to be.

The weeks wore on. I kept snacking on grapes, and walking down hallways, waiting for something to change. Waiting for that feeling to arrive. But it never did.

Now, I really missed Fat Andy. Maybe his mile time was embarrassing, and maybe he had never been kissed. But he knew who he was, and who he wasn’t; what he could expect and what he couldn’t. As it turns out, that sense of self was valuable. Really valuable. More precious than Fat Andy had ever realized. I felt totally lost without him.

So I kept dieting. I kept dieting because I had some hope, however naive, that the feeling was still out there. Maybe just a pound away. I kept dieting because now the diet was all I knew. All I knew was that Skinny Andy ate 21 points. That he was made of cheerios and turkey and grapes and occasional sorbet bars. Which, by the way, had stopped tasting good.

***

One afternoon in late September, at auditions for the fall musical, my friends and I were passing the time by looking through a stack of pictures that Sammi had taken. She handed a glossy photo to me. “Here’s one of you,” she said.

I took the photo and turned it around. I could not believe what I saw. My eyes were sunk back in their sockets. My cheeks were concave and shadowy. My neck was strained beneath sharp collarbones. I looked awful. Awful!

But, no. This was… a mistake. This had to be a mistake. I looked in the mirror all the time. I had never seen this gaunt man.

I called Sammi over. “Sammi,” I whispered. “Is this really what I look like?”

She looked at the photo again, then looked at me, surprised by my confusion. Then, she realized, at least in part, what was going on. She hugged me. “Andy, yes,” she said. “That is really what you look like.”

When I got home that night, I told my mother that I wanted to stop my diet. And that I needed help.

***

Later that week, I was back in Dr. L’s office. She was running late, like always. But when she entered this time, the sight of me stopped her dead in her harried tracks. “Oh my God,” she said. “Why didn’t you call me sooner?”

I told her that I had not made the connection between my diet and my OCD. Dr. L found this hard to believe.

“You count points all day, and you don’t see that as a compulsion?”

I didn’t. The Points didn’t feel like The Rules at all. The Rules came from nowhere and made no sense. The Points came from Weight Watchers. They made total sense. They worked exactly as they were supposed to.

Still, Dr. L insisted that the diet was a manifestation of my disorder. I was not sure that I agreed, but I was happy to work with her again, given our track record. So we got to it. Now, instead of shortening a list, we started to build one. Each week, we tried to add foods back into my life.

My second go at CBT was not like my first. OCD had been a fast-paced, triumphant victory. My diet homework proved much harder. It took me three weeks just to start eating honey graham crackers (3 points) instead of sorbet bars (2 points) for dessert.

For all of tenth grade, I worked to become whole again. I missed Fat Andy the entire time. I missed the way he laughed at himself. I missed the way he understood himself. I missed the way he protected me. My weight, I realized, had been a shield. Skinny brought desires and expectations that were never meant for fat. Without the extra pounds, I was left vulnerable and exposed. I was left alone to chase, point by point, pound by pound, all those things that were meant to be true for boys who wear mediums.

***

For a long time, I could not forgive myself the diet. I hated that I let Stranger-Jock get the best of me. I allowed him to steal Fat Andy and all his wonderful gifts, all because of a single oink uttered during a pointless mile run.

But in time, I healed. Though I will always miss Fat Andy, I don’t know that he was someone to hold on to forever. I think, now, that he was someone to learn from. His lesson was not how to tell a fat joke, or how to make a Waffle sandwich. Fat Andy’s lesson was about self-love. When I think of him, I remember what it was like, to love myself fully. To know my flaws and to accept them; to know my strengths and to wield them. To apologize for no part of me. When I think of Fat Andy, I remember that I have, somewhere inside, the capacity to love myself as he did.

I think losing Fat Andy may have been inevitable. Even had I stayed fat, I don’t know that Fat Andy could have stayed with me forever. I was going to betray him, eventually. I was going to grow uncomfortable with his self-love. I think we all betray our self-love that way, at some point, as we grow up. And maybe that’s how it’s supposed to be. Maybe we are meant to know self-love, then to lose it. So that we can remember it. So that we can miss it. So that we can want it back.

I left my self-love at Fat Andy’s last run. It’s somewhere near a track, after four laps on a chilly spring morning, my freshman year of high school. After that, Fat Andy went away. I’ve missed him ever since. I try to get back to him. I try to find that place: that place where I might love myself fully, the way he once did, in the happy and heavy days of our youth.

***

I have no idea what kind of place you are in, reading this. Perhaps you are where I was, working to love yourself fully. If you are, I won’t say: you’ll get there! I can’t say that. That has not been my truth. I’m in my thirties now, and for me, self-love is still an unpredictable and ongoing journey. Some days I feel close to it. Other days, I feel really far. Some days I feel skinny. Other days, I feel fat. On some days, I’m special; on others, I’m average.

So when it comes to self-love, I won’t make promises. Very little seems certain. But If you’re on that journey, I do want you to know that you’re not alone. I think most of us are right there, running alongside you. I definitely am. (I do promise that I’ll never slap your butt and oink at you. What kind of a JERK does that?).