The Rules began in prayer.

I wasn’t a very religious kid, at least not in the traditional sense. Mom and I were a certain kind of Catholic. I called it “Easter-Christmas Catholic,” because we went to church only twice a year, on those big holidays. I got the sense that we weren’t the only Easter-Christmas Catholics in town.

I also earned my big sacraments. In Second Grade, I attended CCD class for a few months; whatever was required to take my First Communion. The Body of Christ tasted like Rice Krisipies, as Mom had promised it would. I reappeared for eighth-grade Confirmation classes, which were on Wednesday nights. This was a terrible inconvenience to my friend Emilia and me. We were fascinated by a new Wednesday show on the WB (now the CW) called Dawson’s Creek (Don’t come for me… the first season was legitimate and I stand by that claim).

Though my Church and CCD attendance were spotty, I did speak to God a lot, and not just at night. That was my interpretation, anyway, of this feeling I had: the feeling that someone was listening to me, somewhere on the other end, as I carried on big conversations in my head. I still feel that way. I have this intuition that something is kind of everywhere. It’s maybe scientific, like magnetic waves; or maybe spiritual, like God; or maybe science fiction, like the Force from Star Wars.

Anyway, until the end of eighth grade, my nightly prayers reflected my broader approach to religion: leisurely and low-stress. Sometimes I kneeled, sometimes I didn’t. Sometimes I recited the Our Father, sometimes I said the Hail Mary, and sometimes I just made something up. If I missed a night, I didn’t worry about it.

Then, one night, seemingly out of nowhere, my prayers changed. A voice – my own, but not my own – said:

“Three Our Fathers. And Three Hail Marys. Or else.”

It was weird. But I listened. It wasn’t so hard to say six prayers every night. I was lying in bed doing nothing anyway.

That was the first Rule. Soon, more arrived. Many, many more. As it turns out, there were Rules for everything – not just for my prayers. Here are some examples:

- The Calculator Rule: Before you take a quiz, type 100 into your calculator. Press the equals button. Close the calculator. Or else.

- The Orange Juice Rule: When you shut the fridge, stare at the orange juice. Make sure the carton is the last thing you see. Or else.

- The Reading Rule: After you read a page in a book, review the final word from each paragraph. Choose the most important word. Stare at it and blink three times. Then, turn the page. Or else.

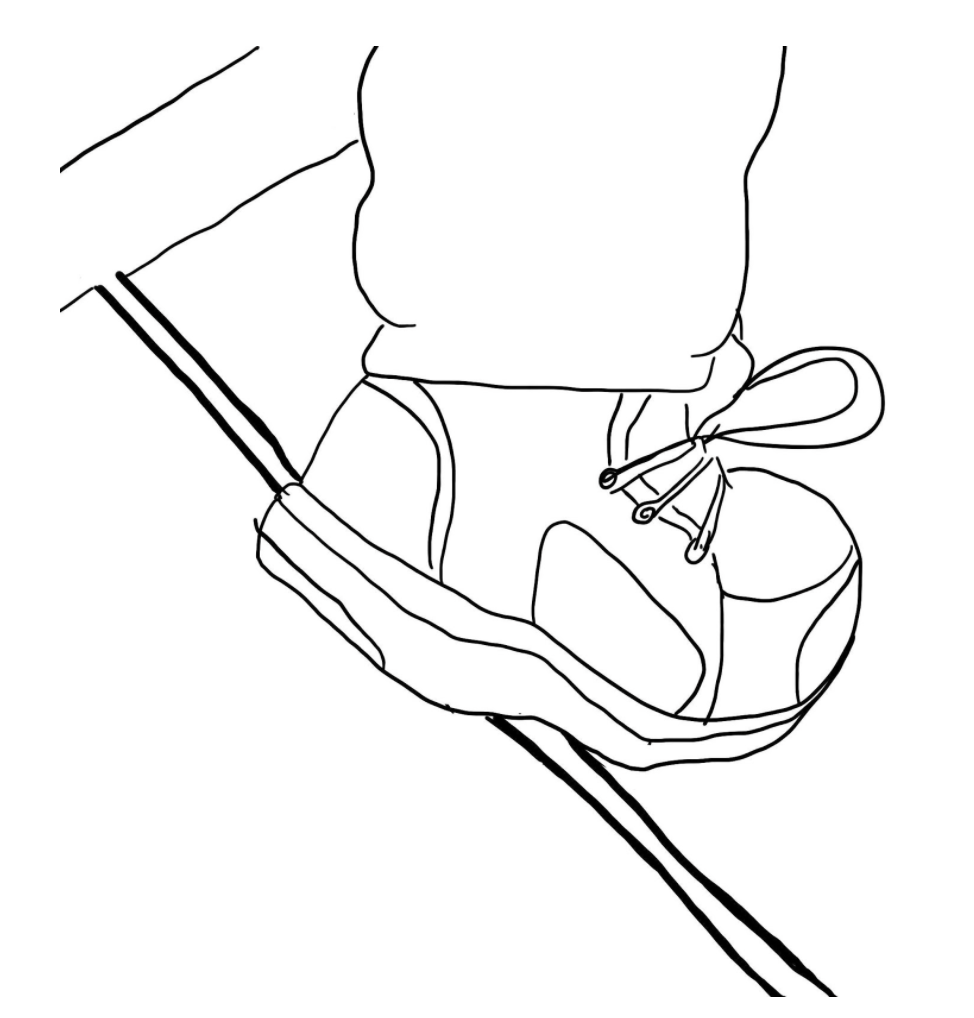

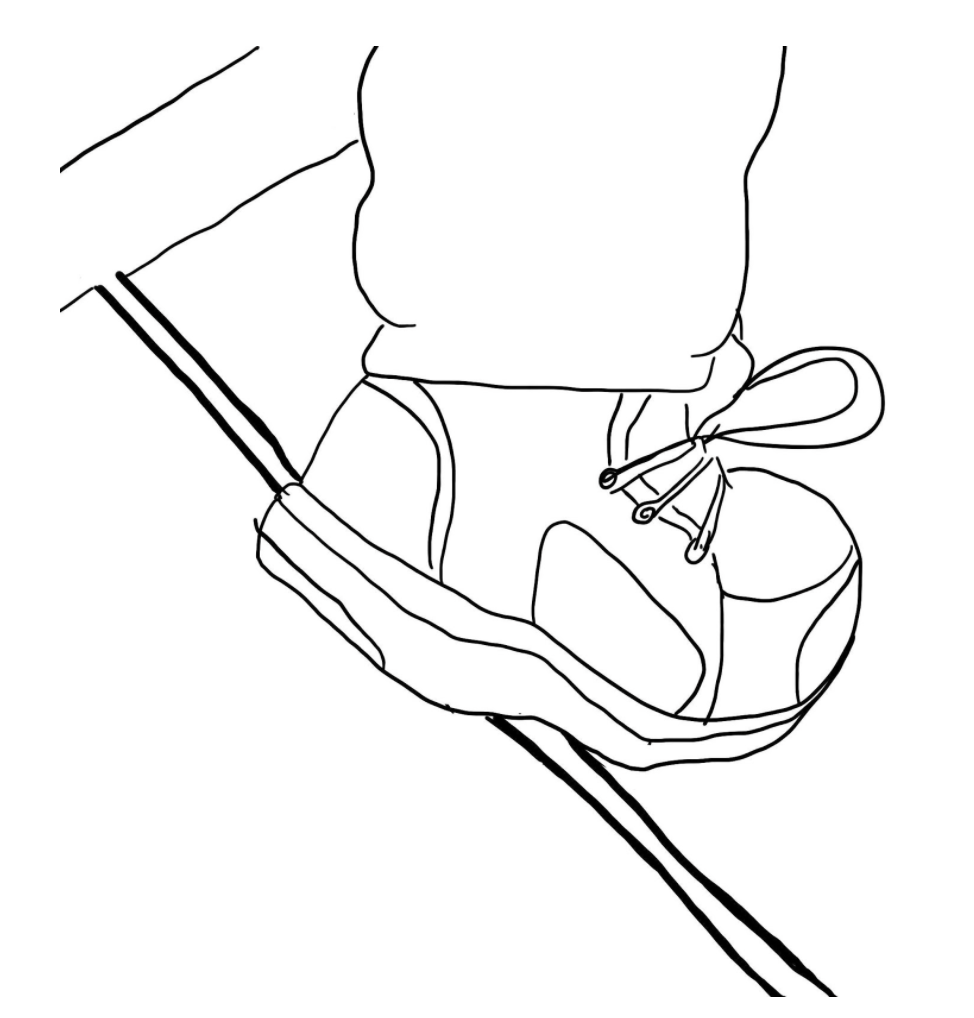

- The Sidewalk Rule: Don’t step on sidewalk cracks (or tile lines, or any kind of linear marking on any kind of floor). Or else.

Or else. Or else. Or else.

All The Rules made that same, vague threat: Or else. That was their power. If I did not do as told, something terrible might happen. The Rules never said what. But I knew it was something really bad. And I believed them, even though I knew my fear wasn’t rational.

Sometimes in life, I believe things because they are rational. They make sense. But other times in life, I believe things because they feel a certain way, even when I can’t justify them logically. Even when there’s no evidence to back them up. They are different kinds of knowing: Thinking-knowing and feeling-knowing.

The Rules were a case of feeling-knowing. I “knew” they were crazy, but I also “knew” they were powerful. They were strong and ruthless. I genuinely felt that I had to obey them. Plus, their demands seemed reasonable, on the whole. Step on cracks? Blink at OJ cartons? These were small prices to pay, to protect myself against or else – whatever that meant.

So I followed The Rules. I followed them very closely.

I said my prayers three times.

I punched in calculator codes.

I blinked at words.

I stared at juice.

I stepped over cracks.

I counted tiles.

I wrote alphabet strings.

I did all that and more. I was careful and quiet and nobody noticed.

It sounds strange, I know. But it was easiest that way. If I did as The Rules asked, they left me alone. They were only loud and threatening when I resisted or stumbled. I found ways to manage, and once I normalized The Rules, The Rules felt normal.

I graduated middle school. Summer came. The Rules, unchallenged, grew in size and number. Still, I managed. I stepped and blinked and counted and stared. I followed the rules all day: in the mornings, while I worked at the local day camp; in the afternoons, while I strolled around town with my friends; in the evenings, when I rehearsed for the Summer Theater show. Somehow, everything was normal, just as it should be, except that the Rules were everywhere. They grew with confidence, habituating and multiplying, enjoying their free and unfettered reign.

Then August came, and The Rules met an opposing force at last:

My summer homework.

Summer homework was an unlikely foe. The Rules had bossed my homework around all spring. And my summer homework assignments were nothing special: Cornell notes on a history textbook, comprehension questions about Of Mice and Men, a few linear equations. The Rules had seen all this before.

These homework assignments were only different because they were for ninth grade. But that was a critical difference, because ninth grade classes were high school classes. They went on your high school transcript. Now, that was a big deal. Colleges, I knew, cared a lot about your high school transcript. And I really cared about college.

I ached for the Ivy League. It was my dream to earn admission to one of those schools. Where I grew up, on Long Island, college was bigger than football. Everybody was always talking about college. When seniors got into Harvard or Yale or Dartmouth or Penn, they screamed and cried and ran around the hallways. Their names got published in the local paper. When seniors didn’t get into these schools, they screamed and cried and went home early, devastated. Everything in my world suggested that if I wanted to be important or rich or famous someday (all of which I wanted to be), the Ivy League was essential.

So when I sat down to do my ninth grade homework, I wasn’t thinking about ninth grade. I was thinking about Harvard and Yale. I was thinking about transcripts. And I was thinking about The Rules, which were becoming a big problem. The reading, scanning, blinking, erasing, rewriting – they were slowing me down. Simple assignments were taking me hours to complete. How could I possibly make As, working like this? And how could I get into the Ivy League without As? The Rules were putting my whole future at risk!

I had to stand up for myself. It was time to cut out The Rules.

I was confident, at first. How hard could it be to conquer fake rules? After all, they started and ended in my own mind. They were mine to control. Enough!, I told myself. Finish the page and turn it. Don’t reread. Don’t blink. Get yourself together.

But it was not so easy.

The Rules were nimble and clever. They knew my fears and turned them against me. “Turn the page. Reread. Blink. Or else…” they said, louder than ever. “Or else, you will NOT get into the Ivy League. All because you did not want to blink!”

My thinking-knowing told me that these threats were empty. But when I tried to break a Rule, my feeling-knowing washed over me. My muscles tensed, my breath shortened, and I understood, somehow, in irrational yet certain terms: my whole future hinges on rereading that page and blinking at the right word.

So I gave in. I read. I reread. I blinked.

I obeyed.

I tried again. I thought maybe some Rules were weaker than others. I thought I could start with the easy ones, then build back to the homework. I tried the orange juice, the calculator, the sidewalk cracks. But whenever I tried to break a Rule, my sour feelings roared, and I fell in line. The Rules strengthened and multiplied.

Things got really bad. My mind frayed. My days lost joy. And, worst of all, my homework was not getting done. I could not start high school with my homework undone. The Ivy League was on the line!

I needed help.

Finally, after months of hiding, I exposed The Rules. I told on them to my mother. I did so in the car, on the way to rehearsal. I preferred the car for difficult conversations. Less eye contact.

“Mom,” I whispered. “I think I have a problem.”

“A problem?” she answered. I had caught her off guard. “What kind of problem?”

I did not have a name for the problem. Instead, I described a few of The Rules, the simpler ones, to illustrate.

Mom grew worried, fast.

“How many of these rules are there?” she asked.

“A lot,” I said. “There are lot.”

“Like five, ten?”

“I dunno,” I said. “A lot.”

“And how often are they… like, how many times a day…”

“All the time,” I answered quickly, and maybe too honestly. I knew my mother, and I knew that this would hurt her. She would wonder how she had missed this. Because The Rules sounded big and demonstrative and unmissable.

She kept asking versions of how many and how often until we got to rehearsal. As I left the car, she told me she loved me and thanked me for speaking up. She added that she was going to call Allison, my old therapist, when she got home.

***

From ages three to nine, I went to Talk Doctor on Tuesday nights. Talk Doctor is what my mother called Allison, my therapist. It was her way of explaining therapy to me. Talk Doctor was a place where I could say anything, where I could share any of my thoughts or feelings, especially the ones that might be bothering me. Talk Doctor, she said, was a safe place.

When I got older, Mom explained that she took me to Talk Doctor on account of the divorce. But that was very much lost on me at the time. I was only three, after all. To me, Allison was a super nice lady with an office full of interesting toys. Every week, I got to play with the toys of my choice, and Allison played too, and we talked while we played. I was happily oblivious to any therapy taking place.

Arriving back at Allison’s office, at age fourteen, was both wonderful and bizarre. The room had gotten smaller as I had gotten bigger. I sat in my familiar chair. To the right, the same dollhouse. To the left, a bucket of plastic animals, including a well-maned, mid-roar lion, who I remembered well. It was comforting to be back here, in a room where I had played so happily. But it was strange, too, to be a kind-of teenager, amidst old toys and memories.

Allison and I caught up on the past five years. Eventually, we got to my problem. I described The Rules again, in more detail. I told Allison everything. A Talk Doctor was someone you could trust.

Allison listened, nodded, and asked a few clarifying questions. I could tell that she wasn’t too surprised by much of what I was saying. Based on what I had shared, she renamed The Rules: Compulsions. And she told me that, most likely, I had developed something called Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. I immediately thought that this was a great name for my problem. Obsessive, Compulsive, Disordered. That for sure captured my life these days.

“What next?” I asked.

Mom joined us, and Allison recommended something called Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. She drafted a short list of Talk Doctors who specialized in it.

“But Allison, can’t it be you?” my mother asked, earnest and anxious, half-joking, half-sincere. We had both hoped for Allison. Someone familiar would have been nice at this uncertain time. But we understood that Allison worked with little kids, and that I was not a little kid anymore. Though I certainly felt like one, sitting back in her office, telling her my secrets, wanting to reach for that rubber lion.

***

Later that week, I was in a new office, waiting for my new Talk Doctor: Dr. L. Her office had a similar layout to Allison’s, except there were no toys. I sat facing an oversized, black leather chair, which overwhelmed the tiny room. My feet tapped on an oriental rug, which was also too big for the room. It curled up against baseboards on one wall and metal filing cabinets on another. I studied its intricate patterns, swirls of red and purple and blue, which wrapped around one another, weaving in and out, in and out.

Finally, Dr. L appeared at the door.

She intrigued me straight away. She had short, unkempt, blonde-gray hair. She wore an impossible number of layers, floral print upon floral print, all beneath a brown vest. She seemed in a rush.

“Hi Andy,” she said, short of breath. “I’m Elaine. Nice to meet you.”

I stood up and stretched out my hand, and she rejected it, motioning with her flailing arms that I should sit back down. “Sit, sit,” she said. “No need for formalities here.”

She eased into her big leather chair. I noticed her loud socks. They had horizontal stripes in bold shades: tangerine, fuchsia, cerulean. Her shoes, by contrast, were solid black.

We began.

“So,” she said, reaching for a yellow legal pad and a pair of purple reading glasses. “Tell me what’s going on.” She uncapped her pen.

Dr. L lacked Allison’s warmth, but I trusted her, partly because she was a Talk Doctor, and partly because she seemed so comfortable in her own skin. I described The Rules to her.

“Mmm hmm,” she said. She capped the pen and moved it and the legal pad to the side. “Andy, let’s try something.”

She turned to her desk and reached for a giant chocolate chip cookie, which I had not noticed. She took the cookie out of its waxy sleeve and placed it on the floor between us. She stood up. She lifted her right foot, then slammed it down, crushing the cookie into the colorful rug. She swiveled her foot back and forth. I watched as her black shoe pressed crumbs into red and blue and purple swirls.

She sat back in the chair and pointed at the wreck.

“Does that bother you?” Dr. L asked.

I stared at the mashed cookie. Did this bother me? Yes. No. Maybe? I mean, this was just … this was really weird.

“Bother me?” I said, buying time.

“Yes. Does it make you … uncomfortable?”

Uncomfortable? Sure. Definitely. A smashed cookie on an expensive rug is categorically strange. Not comfortable at all.

And what did this crushed cookie have to do with me? Was this a test or something? I looked up and saw that Dr. L was watching me, her eyes peeking above her purple rims. I felt like a lab rat.

Two could play this game. I hedged. “It bothers me. But just a little.”

“I see. Should we clean it up before proceeding?”

“No. It’s fine. Unless you want to.”

“No, I don’t want to,” she said.

She paused, then looked right at me.

“Andy.”

She leaned forward.

“Would you eat that cookie?”

Eat it! Game over. “No!” I said, then laughed.

She smiled, and took a note, and my first session of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy had begun. We carried on in the company of a crushed cookie.

That cookie made for an incredibly bizarre introduction to CBT, which is strange, given that CBT turned out to be one of my life’s most straightforward endeavors. Dr. L, in her frenetic prints, amidst scattered crumbs, laid out a simple, step-by-step program for me:

“First, list all your compulsions.”

Easy. I knew them inside and out.

“Second, rank your compulsions, weak to strong.”

Not so easy. They were all pretty strong. But I did my best.

“Third, you have homework. Take your weakest compulsion.”

Okay. Sidewalk cracks, maybe.

“By next session, break that compulsion. Step on the sidewalk cracks.”

Okay. How, exactly?

But there was no strategy. No advice. The session was over. I thought maybe we had run out of time. Maybe we had wasted too many minutes on the crushed cookie, which was still lying there in a hundred pieces. I was unclear how I was supposed to do my homework, having learned nothing new. But it was time to go, so I thanked Dr. L and left. I had nothing but a goal and a deadline.

Turns out, I had what I needed.

As I walked back to the car with Mom, I eyed the sidewalk cracks. I thought of my homework and of Dr. L. I decided to get started: I decided to step on a crack. I expected the Sidewalk Rule to put up a fight, to spin its terrifying logic. But, to my surprise, it did not. It offered only a meager defense. A little tension, a quiet or else. It wasn’t enough. I stepped on one crack. Then the next. Then the next.

I felt great. I had already done my homework! And, more importantly, I had broken my first Rule.

Maybe. Better not count my chickens, I thought. Let’s see how tomorrow goes. Maybe I was on some kind of therapy high. The Sidewalk Rule had fought valiantly and victoriously before. Tomorrow, it might fight back.

But the next day at work, I stepped on hallway tiles. In the afternoon, I stepped on more sidewalk cracks. That night, at rehearsal, I stepped on every line formed by the stage’s old wooden boards.

I really had broken my first Rule. I couldn’t wait to tell Dr. L.

***

The following week, Dr. L entered her office in the same harried manner. She was dressed in more floral layers and the same brown vest. “How did it go?” she asked, right off the bat.

I was ready. “Great!” I said. “I stepped on all the cracks. Sidewalks, tiles, floorboards. The whole week long.”

“That’s good,” she replied, uncapping her pen and reaching for her purple glasses. “Very good.” She took notes as I filled in some details. Then we talked through my list. We chose the next week’s goal: The Orange Juice Rule. I left the office energized.

That’s how CBT went. It was simple, clean, easy. I picked a rule, I left the office, I conquered the rule, I came back. Week by week by week. OJ to calculator to prayers. The process was not gradual or difficult. It felt like the flip of a switch. In just a few weeks, the once-all-mighty Rules became passing whispers, shadows of their former selves.

By October of my freshman year, the list had run out. We were done. I graduated from CBT with Dr. L’s approval and well wishes.

***

On the surface, my OCD journey had been quick and triumphant. I felt proud of what I had accomplished. Tackling these homework assignments, I had been fierce, surgical, and unapologetic. I had displayed superior focus and discipline. I was excited: my performance, I thought, promised great things for my future. If I could conquer OCD in a matter of weeks, what else might I will myself to do? What other victories lay in wait?

I left CBT free of compulsions and full of confidence. It had been a successful and affirming experience.

For the most part.

There was something else to it all. I could feel it, though I tried not to. There was something faint – a sliver of darkness – lurking at the fringes of my confidence and success.

At the time, I could not make sense of this darkness. I was too close to it, and I was too young. But I felt it. I knew that I had learned something important about myself in those sessions with Dr. L, something beyond compulsion management. It meant something, that I had only told my mom about The Rules because I was anxious about college. It meant something, that I had struggled with The Rules for weeks; but that when a woman, a practical stranger, came along, and turned my cosmic struggle into a homework assignment, I stopped struggling. I stepped right on those cracks. It meant something that I trotted back to her office week after week, eager to tell her that I had done my homework, again and again.

Looking back, I can see, now, what I was beginning to learn. I was beginning to learn about my complicated relationship with achievement and approval. I had known that I was the kind of kid who wanted all As; and that I was the kind of kid who really liked praise. My battle with OCD began to reveal just how powerful these desires were. How much they defined me. I was an achiever, and I was a pleaser. That’s why CBT had such a dramatic effect on me. There were goals and there was a person to impress.

Achieve.

Please.

These were, perhaps, the real Rules. Rules on a whole different scale. Not compulsions, but life forces. Rules that directed me not to blink or to count, but to do, to act, to be.

Such Rules – they did incredible work. They focused me and strengthened me. They promised great things.

But there was that darkness to them. Darkness in the way they had consumed me and changed me, so quickly, at the slightest invitation.

Though it would be years before I named them, Dr. L’s office is where I first met my Achiever and Pleaser; where I began to feel their power and weigh their complexity. Together, we had handed OCD a crushing defeat. Leaving that office, I was confident and proud. But I was also uneasy. I sensed that the years ahead might not be so simple for us. We were very strong, and we were a little scary: my Achiever, my Pleaser, and me.